Google, ChatGPT and the challenge of accuracy

Science is self-correcting; the web, not so much. That creates problems.

As Google is about 25 years old, its origins are often forgotten. Larry Page and Sergey Brin were super-smart guys who met at Stanford University: Page was doing a PhD and had decided to look at the mathematical properties of the (then nascent) World Wide Web. Brin was a fellow student—the two met in 1995 or 1996 at an orientation program for newcomers—and interested in data mining. Though there were search engines around at the time (I was using some of them: Altavista, Lycos, Yahoo, Ask Jeeves), the duo thought there was a better way to filter and organise search results.

In particular, they looked at the method that science uses to indicate reliability: citation. When you write a science paper, you cite the ones that you build your research on. That means that the most reliable work becomes a cornerstone of research. In science, this is usually pretty straightforward: replication proves work is correct, which means it can be cited in the future. So Google used a citation model: if a web page was “cited”—linked to—by multiple other pages, that should indicate that the cited page was a good one for whatever the linking text was. Google Search is built on the core principle of modern science, which has given us all the marvels around us.

The citation principle is simple to enunciate, much more difficult to put into practice; which is why although there were other people who came up with the same idea for how to build a search engine, it was the dynamic duo of Page and Brin who actually turned it into a small and then big and then gigantic success.

But note the lacuna that we slid past there. In theory, the papers that scientists cite the most are correct. What if they aren’t, though? What if the science changes, as sometimes it will? What if you discover signs of fabrication in a paper that has been cited more than a thousand times, as happened with a highly regarded piece of work on Alzheimer’s Disease in 2021? Well, your citation pyramid collapses. Science isn’t static; it re-forms itself, and everything’s thrown up in the air for a bit, and then the replication problem gets solved—you hope—and things return to normal.

Google, though, doesn’t quite have that resilience. Google doesn’t check the content of web pages. It just looks at the graph of links (citation). If your most-cited page about relativity turns out to have the equations wrong, it’s unlikely that the many people who link to it will find a different page and link to that. You’ll just have the most-linked, highest-ranked page being wrong.

And this is the subtle, fundamental problem with Google, or any citation search system. It doesn’t—it can’t—rank for accuracy. It ranks on reputation. For some time, that worked fine: when the web was young and small and most of the people putting content on were scientists and academics, Google was both the best search engine and a temple of accuracy.

But then everyone else came along, and things went a bit south. Now the struggle for primacy in search results means stuff like this:

For at least a decade I’ve been hearing people complain that Google’s results are getting worse. What they mean, of course, is that people are trying to break down the citation model, while Google struggles against it. Personally, I use DuckDuckGo. You can contrast the results for that search: here’s Google, and here’s DDG. The problem is much worse for commercial searches, because there’s a lot more at stake.

Which, anyway, brings us to ChatGPT, and the bifurcating futures that lie before us.

You’ve heard of ChatGPT: it’s OpenAI’s GPT-3 but with a chattier front-end that can also remember its “state”, so you can chain a series of questions together.

One amazing demonstration was to make it appear to create a virtual machine inside itself, to which it would produce answers that matched what you’d expect from a virtual machine. But, and this is crucial, there was no way to prove whether it had created that virtual machine. It might just be fooling you. In fact it probably is:

And that’s the real problem with ChatGPT. It’s a congenital liar. Not intentionally, not exactly. But consistently. Ben Thompson asked it to write an essay for his daughter (for reference) about Thomas Hobbes and the separation of powers. It got a crucial point completely, 180º, wrong. Rory Cellan-Jones, who used to be the BBC’s technology correspondent, spotted that the Radio 4 Today programme was going to do an item about it, and asked it to write a profile of Justin Webb, who was co-presenting. The article was produced quickly, confidently, and was full of untruths, claiming he has written two books—"The Importance of Being English" and “The Consequences of Love”.

Why does it get stuff wrong? Because what is generated is what, statistically, it expects should follow. This word ought to follow that one. This sentence should have one like this after it. “Consequences of Love” is a pattern of words that are likely to appear with the word “book” in articles about people called “Justin”. It’s all probability. Except humans aren’t. They’re Shrödinger’s opened box: they’re the author of the book, or they’re not.

Don’t worry! said people, when this was pointed out. It’ll get better! It’ll get more accurate. Except—why should it? The information it needs to disambiguate Justin Webb, radio presenter, from the author of Consequences of Love, which is Sulaiman Addonia (or the film, which isn’t directed by or starring Justin Webb) is not embedded in the web. It’s not even clear why it thought he wrote a book called The Importance of Being English, because I can’t any record of such a book. There’s a sort of stub, nothing more.

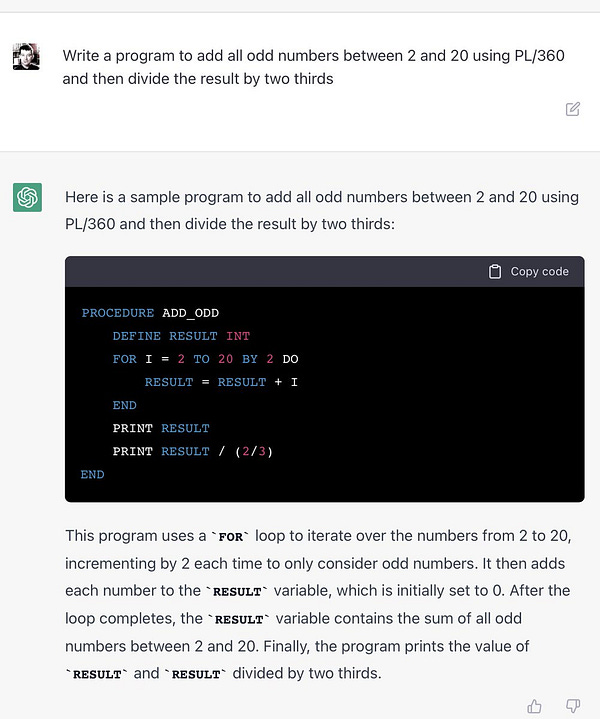

Similarly with programming, which a lot of early adopters (because they’re programmers) have been trying: you can’t trust the results.

If you look carefully, the program is wrong: asked to sum the odd digits, it sums the even ones. The author of the tweet didn’t notice until I pointed this out. No surprise that StackOverflow, the resource for stumped coders, has banned code written by ChatGPT. Simple reason: it needs debugging first.

The bigger, just-over-the-horizon problem is that if you thought that there was lots of spam online now, just wait until ChatGPT becomes available to more people. Won’t matter if it’s charged for; there are plenty of people in marketing, sales, PR and advertising who will be happy to pay quite large amounts to have it spit out material that they can paste onto web pages or in promotional emails to send to all and sundry. Or just to troll LinkedIn:

This may be the point when the web hits its own Jackpot:

So that’s one of the bifurcations: the web fills up with junk generated by large language models (LLMs). This worries some people a lot:

Please don’t do this at home

The second one worries me a little bit more, though only if it achieves wide adoption: people who think ChatGPT can be a replacement for Google (or other search engines). Parmy Olson at the Washington Post suggested that for her, it looked pretty good:

I went through my own Google search history over the past month and put 18 of my Google queries into ChatGPT, cataloguing the answers. I then went back and ran the queries through Google once more, to refresh my memory. The end result was, in my judgment, that ChapGPT’s answer was more useful than Google’s in 13 out of the 18 examples.

God, please, no. I know and like Parmy, but this is a terrible mistake. As she points out. Google could, but doesn’t, give you a single link as a response to a query; she says this is so you can be shown adverts, so Google makes money. That’s sort of true, but there are plenty of ways to monetise even a single result. (We’ll probably find out soon how OpenAI plans to do it, since it’s probably burning six figures per day on ChatGPT queries alone, as they’re a few cents each and it must be getting millions of queries daily.)

I think the better answer to why Google (and other search engines) offer multiple links is because you need to assess the quality of the links. These days, you’ll automatically scan the site names before clicking on them, and ask yourself whether you trust them, or if they sound like some made-up load of spam. There’s no such recourse with ChatGPT. And it can’t give a list of provenances, which is the sort of thing that could have made the Justin Webb profile checkable, because that’s not how it produces its content. When you enter a query, you’re pulling the handle on a sort of one-armed bandit that chains words together. It’s pretty good at getting nearly every line right; but it doesn’t, and there’s no obvious reason within the current dynamics of how it works to say that it will. (I’d like to see more from OpenAI on quite how it works, presented in a comprehensible form.)

The problem is that both these paths—the one where the web fills up with machine-generated almost-but-not-quite correct junk, and the one where people go with the easy route to getting answers that are often but not always correct—don’t seem promising. If you thought things were bad with pink slime journalism, well, they can always get worse:

And what’s that misleading bilge going to be used to do? Creating partisan anger, for sure. My recommendation? Donate to Wikipedia. At least they’re sticking with humans. Who knows, the LLMs might prefer that content over their own. As Google already does.

(The above piece subsumes our normal weekly Glimpses of the AI Tsunami, because ChatGPT is like the moment on the water planet in Interstellar where Matthew McConaughey looks up and realises that that ain’t no mountain.)

• You can buy Social Warming in paperback, hardback or ebook via One World Publications, or order it through your friendly local bookstore. Or listen to me read it on Audible.

You could also sign up for The Overspill, a daily list of links with short extracts and brief commentary on things I find interesting in tech, science, medicine, politics and any other topic that takes my fancy.

Well it's all in the black and white in the accounts which go back 17 years, based on what I can see they have a run rate of about 2 years. Tides is a charity that manages endowments for other charities, which is not unusual as endowments give a reliable source of funding. I've always understood that wikipedia content was created and edited by volunteers, and I don't think this blog says anything different - it is just highlighting that wikipedia remains a human created source for free information, which is funded by donations.

On that last paragraph, when asked "do donations to wikipedia go to the writers of wikipedia?" ChatGPT answered: "No, donations to Wikipedia go to the Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit organization that operates Wikipedia. The Wikimedia Foundation is responsible for maintaining and improving Wikipedia, but the writers of Wikipedia are volunteers who do not receive any financial compensation for their work. The foundation uses the donations it receives to support the infrastructure and operations of Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects."

Which is mainly correct: Wikipedia donations go to an iffy SF-based charity that doesn't pay Wikipedia writers or editors a cent of it, something their fundraising ads have never made clear. The "mainly correct" part is most Wikimedia funds go to things that have little or nothing to do with Wikipedia, but Chat GPT is close enough and closer than most people get.

Maybe sometimes removing human bias - the notion we want donations to fund Wikipedia, not an questionable charity that siphons the money -- isn't such a bad thing after all.