Just under a year ago, there was no ChatGPT, and AI illustration programs had only recently begun to capture people’s attention. Even so, I thought there was something worth paying attention to happening with AI content generation, and wrote an article here titled “The approaching tsunami of addictive AI-created content will overwhelm us”. It was quite popular—as in, became the most-read article on the site. In it, I pointed to the growing confluence of AI- and algorithm-enabled systems that were all starting to rise to the top of the technological attention stack. The timing was good for AI; the crypto/Web3 craze was draining away in a morass of fraud and the realisation that coins nobody wants to trade and “unique items” that anyone can copy aren’t the underpinning of any sort of financial system.

At the time, I offered these building blocks to forecast what could happen:

• Companies whose whole business is built around capturing attention

• AI systems capable of producing limitless amounts of content

• AI systems capable of producing believable-looking pictures of humans (and lots of other things)

• Algorithmic systems which will pick content that humans find compelling

• Humans who like spending time watching content they find compelling

• GAN-generated photos already being used for fake profile pics for marketing or, worse, disinformation and espionage.

As I say, this all preceded the public release of ChatGPT, in November 2022, which really kicked everything off. Whereas Google, when introduced, seemed to have a magical ability to find anything on the web, ChatGPT seemed to have a similarly magical ability to discourse on absolutely anything. In the course of about a week, it went from “what’s this?” to “WOW WHAT IS THIS”. It became a byword for AI, and featured heavily on radio and TV shows. The question everyone wanted to answer was: how is this going to affect our world, and particularly jobs and work?

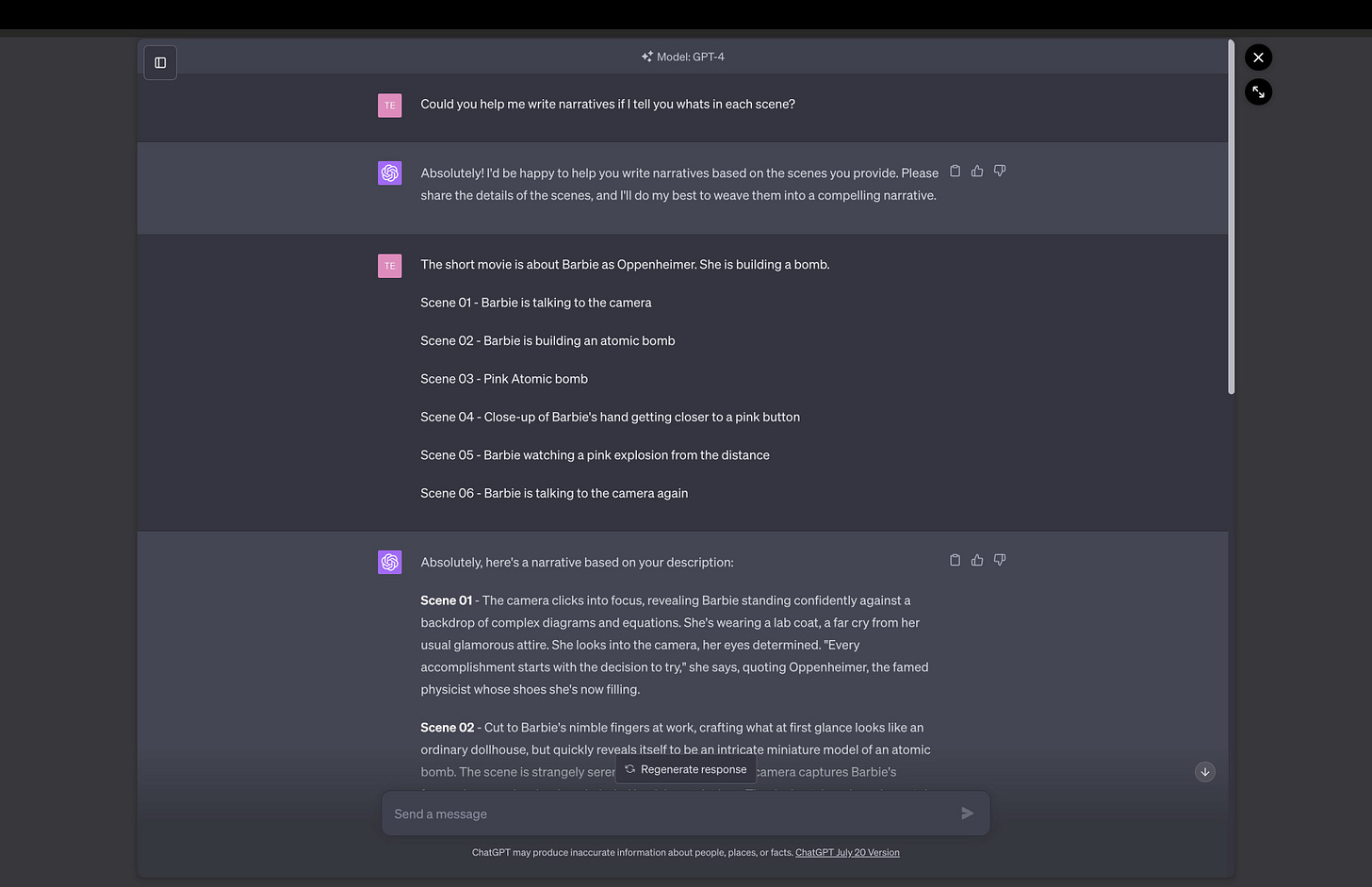

My focus is not so much on the tools themselves, or how they work, but on what they produce. The expansion of their availability is leading to people having a lot of fun. So for now, let’s have a look at some of the fun. There’s this 17-second Barbenheimer video on Twitter, of which its creator says “Here’s how I made Barbie video using only AI”. (The full thread is on Twitter.) She got ChatGPT to do the art direction on the scenes she offered. Here’s what it looks like (apologies: probably illegible on a phone; see caption for example content):

She then put in some retro Barbie pictures, and fed those into Midjourney, the AI illustration engine (which has improved enormously in the past year). Then some colour correction in Adobe’s Lightroom, and then feed it into Runway, which turns still pictures into videos. But wait, it needs a voiceover! No worry, Eleven Labs can synthesise a voice in “American young female”. Roll it all together in Final Cut Pro, add captions, and bingo, you’ve got a short clip of Barbenheimer.

Or there was the much more bizarre “Heidi” ‘trailer’ a couple of weeks ago, which is far weirder than I think any human would expect to create:

And let’s not overlook the Screen Actors’ Guild of America and the Writers Guild of America—actors and screenwriters—who are both on strike, at the same time, and both making demands that AI should not be used in the writing process, and that it should not be used to generate actors.

Meanwhile computer programmers are delighted with the powers unleashed by the new LLM (large language models), which can generate reams of code easily for them, and only need a bit of checking to make sure there aren’t any obvious bugs. But there are downsides: Stack Overflow, the can-you-help-me? site where programmers like to congregate and help each other out, moved quickly to ban recognisably AI-generated submissions, though this naturally raises the question of how you’d identify such a submission.

That points to the real problem with AI content at present: it’s leaking into our world, drip by drip, and identification is difficult. Universities and schools are already struggling to identify chatbot-generated essays on topics. Marketing companies are using chatbots to create marketing emails, and are even experimenting with chatbot-driven voice calls. (I heard one via Twitter, but of course can’t find it now. The chatbot had an English accent, and sort-of echoed back things the person being called had said with a little sales spice added on top. It was a deeply uninspiring call, but probably no worse than some carried out entirely by humans.)

But we’re only at the beginning. I called it a tsunami, and that’s still what I see ahead. Meta has open-sourced an LLM, Llama 2, which is free for commercial use by anyone who isn’t Apple, Microsoft, Google or Snapchat (ie has fewer than 700 million users) and where the download includes model weights. You can already squeeze Stable Diffusion onto a phone; what happens when you can have a self-contained chatbot that doesn’t rely on the cloud for processing on your phone too? What happens when you have a version of Runway that will take a series of photos from your photo library and create a Heidi-style trailer of your holiday or birthday or walk, rather as you presently get the occasional autogenerated slideshow from Google or Facebook or Apple when whichever one decides you haven’t been paying enough attention to the site and the photos you dumped there? We’re literally only at the beginning of this.

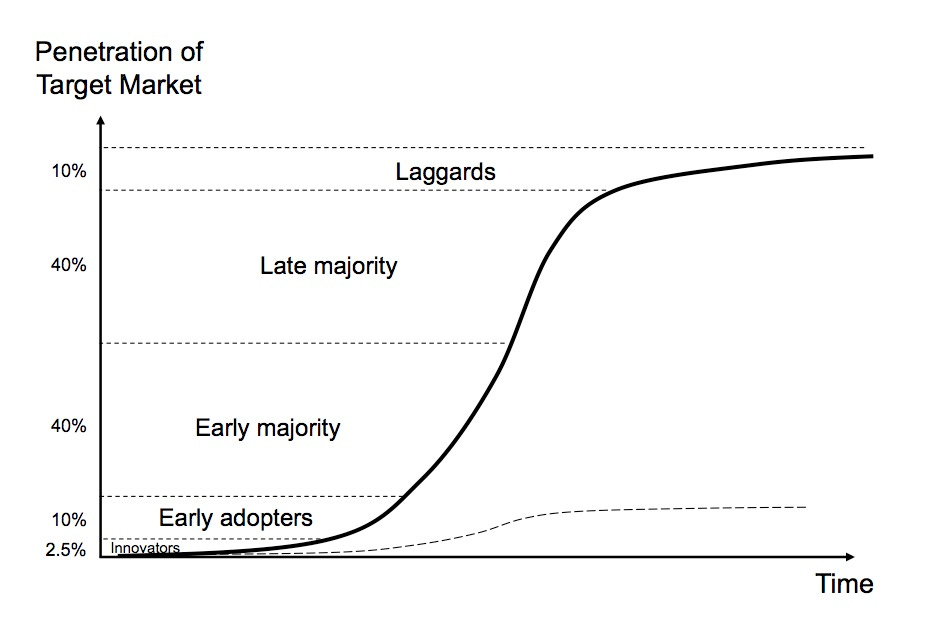

Look at the diagram below, and consider at what times we’ve been on which part of it for two of the biggest technology diffusions of the past 30 years: the internet (fixed and mobile), and the smartphone.

For the internet, the International Telecoms Union (ITU) says that we’ve gone from 16% of the world population being connected in 2005, to 66% in 2022. That means we’ve moved up from just into the “early majority” to halfway into the “late majority” over the course of 17 years.

For the smartphone, we can also start at 2005—the BlackBerry, Palm, Nokia and Windows Mobile devices preceded the iPhone, but sold in nothing like the volumes that would follow in 2007. From there, adoption zipped rapidly up the curve, until now there are 6.8bn smartphones out there, which would be an 85% global penetration rate; except there are multiple smartphones owned by people and companies, so the real penetration rate is somewhere around the same number as the internet, at 66%.

Both those transformational phenomena have happened in 18 years. (Slightly longer for the internet, since it was already at 16% in 2005.) We’ve had Midjourney and its siblings, and ChatGPT and its siblings, for a year or less. A report earlier this month found that 1 in 12 adults (and maybe more children?) have used generative AI for work; that’s about 8% of the population. We’ve climbed out of the “innovators” level, and we’re now firmly into the “early adopters” market. But there’s a gigantic vista ahead which will be filled with all sort of content. We’re starting to get the idea: Johnny Cash singing Barbie Girl, deepfake porn, news websites offering opinion pieces written by ChatGPT, ransomware and associated demands written by chatbots. There are downsides, indeed. But look, you’ll have a thing on your phone that can generate a weird video. Silver linings, right?

• You can buy Social Warming in paperback, hardback or ebook via One World Publications, or order it through your friendly local bookstore. Or listen to me read it on Audible.

You could also sign up for The Overspill, a daily list of links with short extracts and brief commentary on things I find interesting in tech, science, medicine, politics and any other topic that takes my fancy. Leave a comment! Restack on Notes! Do all those interaction things!