Laura Kuenssberg really came to widespread attention as a reporter in 2010 when she became the chief political correspondent of the BBC, and became almost ubiquitous on screen following the close-fought election and subsequent coalition negotiations. After a brief stint at ITV, she returned to the BBC in November 2013 to become political editor of Newsnight—then a current affairs programme which would break stories and provide separate analysis of events. She then succeeded Nick Robinson in 2015 to become the BBC’s political editor, the top news job at the corporation: once again she was almost ubiquitous, as Brexit (2016) was followed by a general election (2017) and colossal legislative logjams for two years, which meant she barely had a moment off screen. And then there was Tory leadership races, and elections, and Covid.

What’s amazing is that she managed not to collapse in a heap, given that the job is utterly relentless. At the end of 2021 she stood down from the political editor job to take up a simpler presenting job, fronting an interview programme on Sunday mornings. (Sunday mornings on terrestrial TV are reserved for three sorts of programmes: religious, cooking and political. One tells you what to do with your life, one tells you what to make for lunch, and the other tells you what you’ll hear on radio and TV news for the next 24 hours.)

This past week, Kuenssberg was going to film a big set-piece interview with Boris Johnson, who has an autobiography coming out next week which the more enterprising booksellers will file under “Fiction”. (Ian Hislop suggests on the Private Eye podcast ep 123 that rather than being called “Unleashed” it should be called “Undead”, because Johnson’s political death has been announced so many times and yet like a zombie in a horror flick he keeps coming back, even when nobody wants to see him again.)

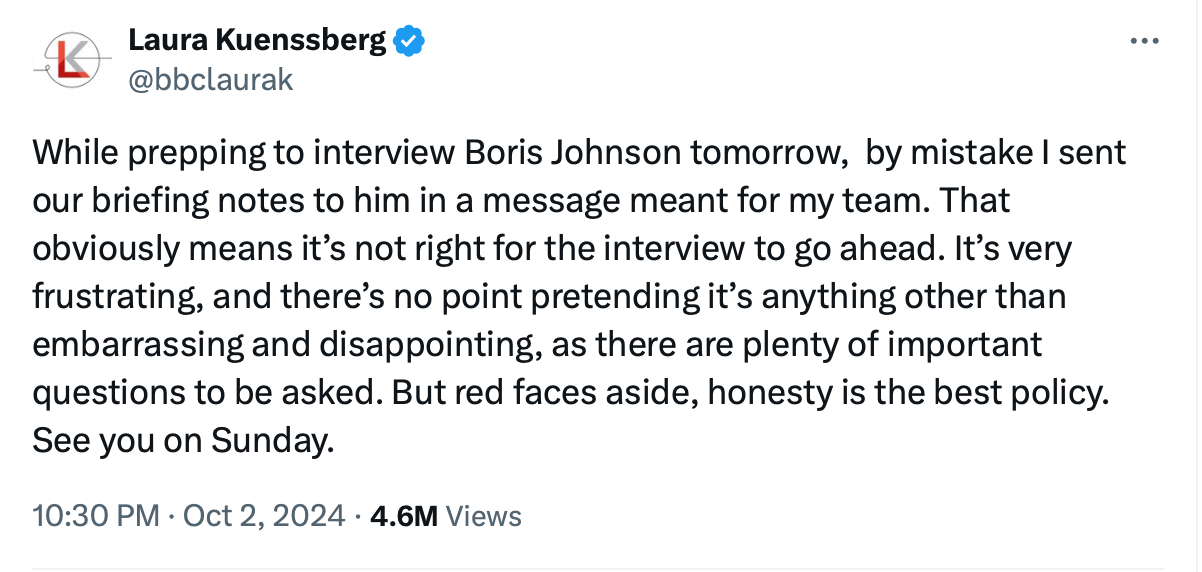

Anyhow, on Wednesday evening, Kuenssberg confessed to a big mistake:

Now in some quarters, Kuenssberg is not flavour of the month—or of any month. She earned the enmity of pro-independence Scots in 2014, because they thought that she (a Scot) had been pro-remain in her coverage. Subsequently in her career as political editor, she was seen as being too close to Boris Johnson, even though that was essential while he led the pro-Brexit movement in 2016, tried for the leadership and failed, got into the Cabinet, tried for the leadership and succeeded and became Prime Minister, and won a huge victory in December 2019 to be cemented as Prime Minister. For the BBC political editor, it’s pretty important to have a professional relationship where you know the top person and those around them.

This of course hasn’t been good enough for many people, who see her as being in Johnson’s pocket (or worse). I’ve had my own exasperations with Kuenssberg’s social media competence, but not in general with her actual journalism.

But let a journalist in the public eye make a mistake, and admit it publicly, and everyone’s off to the races. The replies to the tweet are, predictably, a fission-hot mess, but what got me interested was the quote tweets atop it.

Quote tweets are, of course, the ultimate dunking mechanism, the fairground strength test of internet dialogue: if you hit hard enough, you’ll ring the bell of virality. Here’s a few, picked—necessarily—at random, because of course there’s no sorting mechanism for number of views, or retweets, or anything that might help a researcher on Twitter.

I think you get the general tone: completely unsympathetic. It’s amazing that you can find so many people who have never made a mistake in their working lives: never misdirected an email in an embarrassing fashion, never said the wrong thing at the wrong time.

The weird thing is that the quote tweet was meant to be a force for good, not evil: the idea was it would enable you to add context to the quoted tweet. What we see, though, is that that doesn’t happen. As I describe it in Social Warming,

Whereas a retweet was often seen as an endorsement, either of its content or its author (compelling many people to supplement their Twitter biographies with ‘RTs are not endorsements’), a quote tweet could make absolutely clear that you didn’t endorse the contents. The effect often resembled someone walking out onto a balcony to an adoring crowd and announcing, ‘You’ll never guess what this idiot just said on the telephone! Let me read it back to you!’ Someone with a large following could easily unleash a virtual pitchfork-wielding mob on the original tweeter.

To be fair, amid the Kuenssberg QTs there was one person there who hadn’t come to dunk:

However I had to read a lot to find that one. What really struck me was that for some people, a single bite of the cherry wasn’t enough. You hear about accounts working on their tweets to try to make them go viral. It’s what we could call the hyperbole ratchet: you amp up the outrage, step by step, trying to find something that will work best. For verified accounts, the benefit is that they might be able to make some money from it; for the average punter, there’s just the pleasure, I guess, of seeing something go viral.

I noticed one account particularly—though I think it’s a general pattern—really trying to work on the Kuenssberg stuff. In this sequence, you can see him trying a different variation each time, a few hours apart, trying to catch the wave of outrage like a desperate surfer.

It started with a tweet sent out at 7.46am on Thursday:

This garnered 118k views, 1,200 retweets and 5,400 Likes. A good start! But these things are never done. At 8.54am he had another try:

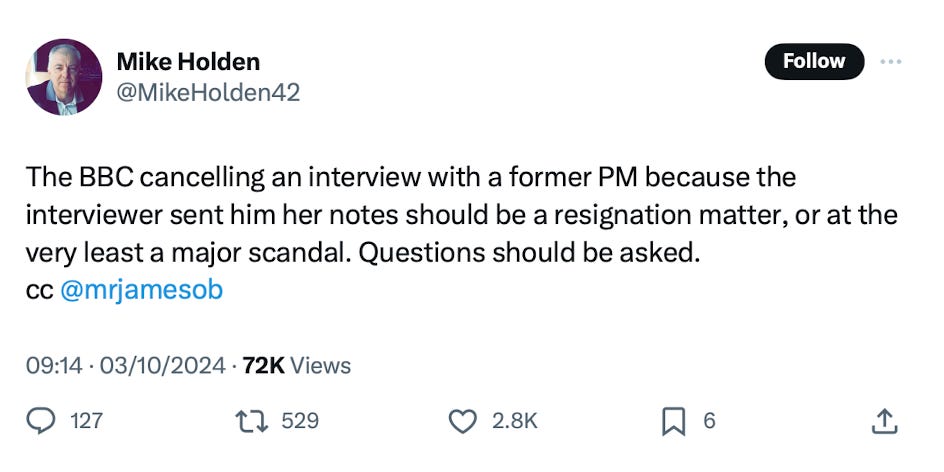

This one only got 7.1k views, 20 retweets and 124 Likes. Not good enough! So at 9.14am he had one more go:

As the data shows, this got 72k views—not as many as the first one of the day, but not bad—and 529 retweets (also less good) and 2,800 Likes (about half what the first one got). Holden has kept on at this like a dog at a bone, though he shifted his focus later in the day to the fabulous hypocrisy of the Tories criticising the Labour government’s handing over of the Chagos Islands, a process which the Tories themselves began last year.

What’s notable about those three tweets though is how it ratchets up the demands. In the first one it’s mildly jokey, as is the second. But by the third it’s “a resignation matter, or at the very least a major scandal.” This is the hyperbole ratchet in action. It’s not enough to make fun of a mistake: if you want to stand out from the crowd, you’ve got to DEMAND! ACTION! NOW! Because, as you’ll have intuited, the great advantage of the hyperbole ratchet is that as you increase the importance you attach to whatever failing you’re drawing attention to, you can then draw attention to the lack of action being taken by the powers that be over the Thing You Have Decided Is Crucially Important. It’s a resignation matter! A major scandal! Questions should be asked! Which logically means that if no resignations are forthcoming, if there is no investigation into a scandal, if questions are not asked, then it is a vile calumny which cannot be allowed to stand!

Meanwhile: someone put the wrong name on a communication, which happens unhappily often because machines try to help us by “suggesting” things. It probably happened hundreds if not thousands of times on Wednesday all over the country, but rather fewer people confessed to doing it. For those who want to make fun of it, the target is a mile wide (I confess to quote-tweeting to the effect that the world will be that much poorer for having one fewer interview with international man of mystery Johnson—how will we find out about his life that has been shrouded in secrecy now?) but it’s not, in the scheme of things, a big deal.

But if you’re on the hyperbole ratchet, it is a big deal, and the next time Kuenssberg shows her face you can be absolutely sure there will be a ton of people ready to remind her of it. We can’t affect that. All we can do is be aware of it, and do our very best to resist or, even better, ignore or make fun of it. Ratchets can be reset, and the best way is to put events into perspective. Not, of course, that anyone on social media wants to do that. Because where’s the fun in being accurate?

Glimpses of the AI tsunami

(Of the what? Read here. And then the update.)

• AI avatars are doing job interviews. Worrying.

• AI means everyone can write a book! Fabulous! So says Nadim Sadek at The Bookseller. Other views are available.

• You want to escape AI online? Almost impossible, says the New Yorker.

• The cool thing about smart glasses is not the augmented reality, it’s the AI. Mat Honan at Technology Review sees lots of potential. (Some hackers turned facial recognition on the move into reality.)

• A counterpoint to expectations: a scientific paper finds that AI chatbots don’t help police write their reports.

• AI crawlers are almost DDOSing sites as they trawl them for content.

• You can buy Social Warming in paperback, hardback or ebook via One World Publications, or order it through your friendly local bookstore. Or listen to me read it on Audible.

You could also sign up for The Overspill, a daily list of links with short extracts and brief commentary on things I find interesting in tech, science, medicine, politics and any other topic that takes my fancy.

• Back next week! Or leave a comment here, or in the Substack chat, or Substack Notes, or write it in a letter and put it in a bottle so that The Police write a song about it after it falls through a wormhole and goes back in time.