And if the chatbot told you to jump off a cliff, would you?

LLM NBG RLY

Hey, it’s tennis season1, and I’m enjoying the tennis from Indian Wells, on the Californian coast. In the round of 16, Britain’s Jack Draper played America’s Taylor Fritz—one a semifinalist at last year’s US Open, the other the beaten finalist at the same event.

But after they had played, ie on Thursday morning, what was their head-to-head record?

If you’re one of the many people who seem to be proliferating right now, then you know exactly where to go to answer this question: a chatbot.

OK, then, let’s go and ask ChatGPT.

Let’s not spoil the surprise of whether that’s right or wrong yet. Let’s ask Grok, the chatbot that is now incorporated into X:

First of all, notice that ChatGPT says they’ve played three times up to March 13. But Grok says they’ve played seven times. Yet then it cites only five results.

Now let’s get the definitive answer, by going to the ATP (Association of [male] Tennis Professionals) site:

This is the reliable source. Five matches: one in 2025, three in 2024, one in 2022.

Grok has the list correct—but says they’ve played seven times. Why?? ChatGPT meanwhile doesn’t know about 2022, or the Munich match, so the H2H is wrong.

If you relied on either of these chatbots for your answers to what is a very straightforward question, you’d go away with incorrect information. And while I haven’t tried every chatbot on the market, you’re welcome to have a go; these two just happen to have the biggest mindshare. And, to repeat, they get stuff wrong. Very simple stuff, like how many items there are in a list.

Which means that when people start using it for more complex questions than tennis players’ win-loss records, things can quickly get very messy.

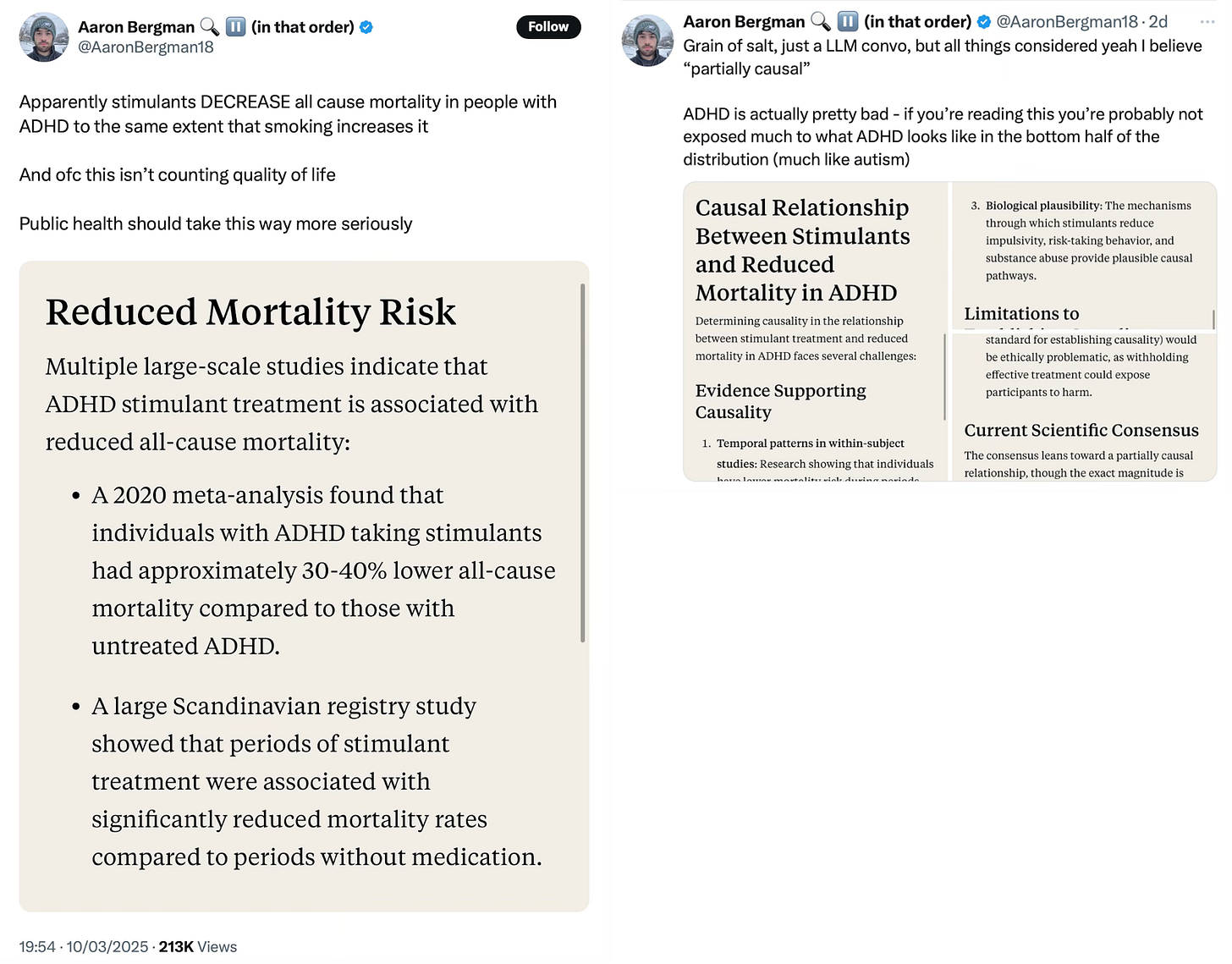

“Just a LLM convo”, huh. It didn’t take long for people to point out that this didn’t make sense (see the comments to the post), such as “That makes no sense. The hypertension alone should have some negative impact on lifespan.”

And an even more relevant question was raised by the Science Banana account:

Followed by the despairing noise that is so common among specialists coming into contact with non-specialists who have used a tool and not quite understood how to use it properly:

Would a computer really just go on the internet and lie? Well yes. Yes it would. That’s because LLMs don’t know when they’re lying. They don’t have any self-questioning systems to determine whether their answers necessarily conform with reality. The chatbots giving the tennis data were working off solid datasets which had been updated in the past few hours, but they didn’t have systems that would tell them whether five matches meant a 2-1 record or a 3-4 record or even what the hell five matches means. Chatbots don’t have a theory of the world; they just put words after each other that seem to be like the words that they found near each other when they were fed with the internet, and then they spit the words that they’ve picked out to you.

The wrong tsunami

Back in August 2022, I figured that there would be an AI tsunami of content which would increasingly tailored to us so that it would be addictive, and we’d lose interest in human-made content. That’s still a problem that could arise—don’t get out the bunting yet—but we now have a much more proximate problem with AI that is also more pernicious: people think chatbots know the answers.

Here’s what someone replied when I pointed out that “asking a chatbot to answer a technical question” was basically outsourcing their brain to an unreliable machine, and that it wasn’t smarter than they were:

When did we go from Googling stuff and following links and checking facts to “of course it’s smarter than me”? This is a worrying trend, yet if you look around on social media, you’ll see more and more people offering screenshots from chatbots of one flavour or another as answers to questions. Have they checked whether it’s right? Probably not. Meanwhile Google is pushing even more AI Overviews, effectively short-circuiting people’s previous requirement to at least browse the excerpts from a few sites to see if they agreed in the answers they offered. (If they didn’t, you needed to look a bit deeper to find out why.)

The problem is that nobody ever disappointed the general public by making it easier to do something. If you give them a box which seems to promise to answer every question immediately, rather than making you browse some results, then they will gravitate to the box. It’s the same irresistible force that drove people to migrate first from vinyl to CDs and then to MP3, from film camera to digital camera to smartphone camera, from mainframe to PC to mobile. Do MP3s sound better than CDs? Who cares, they’re convenient. Do smartphones take better pictures than film cameras? Who cares, they’re convenient. Do chatbots give better answers than a search engine results page and the results therein? Well, look, I care a bit, because having a shared set of facts you can rely on is fundamental to making good decisions about the world. Plus people who are given wrong information by these systems are extremely reluctant to believe they’re wrong. You can show them all sorts of sources, but they’ll insist that the chatbot is correct, not the work produced by humans.

It’s always worth repeating: chatbots are stochastic parrots, putting words together with as little understanding as a parrot. The 2021 paper that coined the word points out (on p616) that the output from LLMs is “seemingly coherent”:

We say seemingly coherent because coherence is in fact in the eye of the beholder. Our human understanding of coherence derives from our ability to recognize interlocutors’ beliefs and intentions within context. That is, human language use takes place between individuals who share common ground and are mutually aware of that sharing (and its extent), who have communicative intents which they use language to convey, and who model each others’ mental states as they communicate.

But, they point out

Text generated by an LM is not grounded in communicative intent, any model of the world, or any model of the reader’s state of mind. It can’t have been, because the training data never included sharing thoughts with a listener, nor does the machine have the ability to do that. This can seem counter-intuitive given the increasingly fluent qualities of automatically generated text, but we have to account for the fact that our perception of natural language text, regardless of how it was generated, is mediated by our own linguistic competence and our predisposition to interpret communicative acts as conveying coherent meaning and intent, whether or not they do. The problem is, if one side of the communication does not have meaning, then the comprehension of the implicit meaning is an illusion arising from our singular human understanding of language (independent of the model).

In other words: we effectively anthropomorphise chatbots’ output. But we shouldn’t, despite the insistent efforts of the chatbot creators to give them the façade of personality (such as Grok, above, using the phrase “my knowledge”). We should distrust them all the time, and be wary of the people using them.

Which, incidentally, gives us our coda. The technology journalist Chris Stokel-Walker got an excellent scoop at New Scientist, using Freedom of Information requests to find out how Peter Kyle, the UK’s technology secretary (a ministerial post), uses ChatGPT.

Turns out that Kyle asked it about why the UK’s small and medium-sized business have been slow to adopt AI (did he think the chatbots somehow talk to each other?), and which podcasts would be best for him to go on to reach a wider audience in the UK. Stokel-Walker was inspired to make the FOIA request after Kyle gave an interview to PoliticsHome, where Kyle said that “ChatGPT is fantastically good, and where there are things that you really struggle to understand in depth, ChatGPT can be a very good tutor for it”.

Oh dear. You know, sometimes life is a real uphill struggle.

• You can buy Social Warming in paperback, hardback or ebook via One World Publications, or order it through your friendly local bookstore. Or listen to me read it on Audible.

You could also sign up for The Overspill, a daily list of links with short extracts and brief commentary on things I find interesting in tech, science, medicine, politics and any other topic that takes my fancy.

Turns out it’s always tennis season, to the slight despair of the players, who last year got exactly four days off between the official end of the 2024 Tour and the start of the 2025 one.

I do think the issue with a lot of searches we do is that we are curious creatures seeking answers in a given moment. We’re in the pub wondering about something, or we’re distracted by a line in a book and get curious on a detail. But at times like those, sometimes having any answer is enough, even if it’s not even the right one. I suspect many people, once they’ve satisfied that human need to gather information, actually don’t care if it’s even accurate or not. It’s like we’ve evolved for finding answers but not necessarily for finding truth.