Hello, the algorithm would like your attention

Plus AI gets into film studios while also making you doubt yourself

Early in September, Elon Musk tweeted this:

Notice how he used the O-word: outrage. Lots of people are so very surprised by what they discover when they open Twitter (I am going to keep calling it that) and find that, by default, the app is showing them the “For You” tab. These are tweets algorithmically picked to engage you—to make you spend time reading them, to reply to them, to quote-tweet them, to retweet them.

How does the algorithm “know” that those are the tweets to show you? Because other people have engaged with them—probably, been outraged by them. Circular reasoning, to be sure, but that is how it works, because there’s always a ready supply of new tweets for people to pore over. You’ll find tweets in there which will test the limits of your outrage: is this one too much? No? Do you linger over it, do you reply to it, quote-tweet it? Then the algorithm will offer you something a little spicier. Do you interact with that? Then something even more tantalising will come along soon enough.

The “outrage” reaction, as I’ve written before, is a fundamental way that social media functions: it’s why social warming happens—because we keep seeing material that outrages us, and there’s a long-term, subtle but undeniable ratchet effect. Material that outrages us attracts our attention because we’re primed, as social animals, to notice things that breach our social rules.

But, you might be asking, why do we need an algorithm to show us annoying tweets that we might want to interact with?

One can see the answer to that quite clearly by going to an app such as Bluesky, which just passed 10 million users. (I was in the first 88,000. Definitely early adopter disease.) Even though there are plenty of people there who have moved over from Twitter, it’s not that easy to find people who you want to follow, and even when you have added a good number you’ll discover the classic problem with non-algorithmic (aka “reverse chronological”) feeds: some people post a lot but are rather boring, while the people who produce interesting posts tend not to do so very often, and some of the most interesting and prolific posters might be outside your network. And then there’s a lot of stuff in the middle which is just “blah”. When you have a relatively small network, as Bluesky presently is—and as Twitter used to be—then that problem is amplified. Result: people get bored quickly and log off for somewhere more interesting.

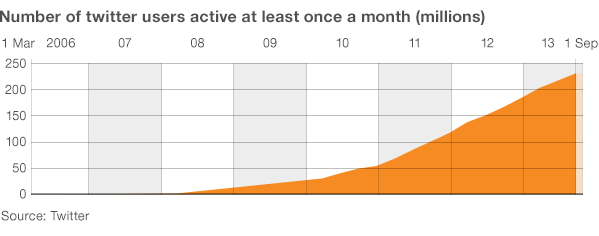

For reference, Twitter passed the 10 million mark some time in early 2008, only a couple of years after it launched:

Bluesky only really launched as a network in February 2023, which means it’s at about the same place in the timeline as Twitter was in late 2007 (Twitter launched in March 2006). Launching now rather than in 2006 has given it advantages—it’s much easier to come to people’s notice, everyone has smartphones and is familiar with the idea of downloading apps, it’s a mobile-first world, you can assume data connectivity, you know the rough order in which to add features—but also disadvantages, principally that there are many more established networks out there which don’t want to give up their users.

Facebook was in fact the first to realise the problem with un-algorithmic content, only two years into its existence. I wrote about it in Social Warming:

In any large enough group, some people will post a lot more than others. If someone boring is churning out their fifteenth post of the day about potholes in the roads, you might not care, but they’ll dominate the reverse chronological format. Pretty soon you’ll grow bored, and move on to something else—perhaps Twitter?

Facebook realised that its busiest users could actually be the biggest challenge to growth. The problem resembled that of search in the years before Google, when search engines ranked sites based on how many times they used a particular word or phrase: the ‘noisiest’ pages would appear top in search. Only when Google began ranking sites using the ‘PageRank’ algorithm, which measured how pages pointed to each other as a measure of their perceived authority, did web search become effective.

The group at Facebook, which included Mark Zuckerberg, Aaron Sittig, Adam Mosseri and others, devised a system that revolutionised social media posts in a way comparable to Google and search ten years earlier. They called it ‘EdgeRank’—a cheeky poke at the giant company—and created something that would wipe rivals off the web. EdgeRank was a system that considered each piece of content, which Facebook called an Object. The Object’s ‘Edges’ were given values: your relationship to the poster (friend, family), the type of content (text, photo, video), how you had responded to an Object like that previously, how many interactions the Object already had, how old it was. Every Edge value also had a weighting that influenced how likely the system was to show that Object to you.

This is why the Twitter algorithm—which to a large extent predates Musk; all that’s happened since he took over is that the proportion of absolutely outrageous content on the site has gone way up, because those who post outrageous content (especially with paid-for accounts, who get rewarded based on views) are far more numerous, and those who would offer more pacifying content have moved away to places like, well, Bluesky.

(Although I’ll always recommend the Niall Harbison account, which has tales of rescue and rehab of street dogs in Thailand: he mends them and they have mended him.)

With a small network like Bluesky, having an algorithmic feed is almost essential: it’s the best way to get people to find new content and users they might like to follow. (Hence I spend most of my time on its “Discover” feed or the “Popular with Friends” feed.)

But using an algorithm can have a negative effect: Threads, which is now up to 200 million users, is algorithmic by default, and it has been taken over by ragebait:

On pre-Elon Twitter, retweets were the main way a post would spread. This rewarded things like the Ellen Oscar selfie, Dril jokes, and sweeping political statements. You want to retweet a funny joke — not reply to it.

But a personal anecdote asking for advice? You're compelled to reply.

I wanted to test this out for myself on Threads. I made a handful of advice-seeking posts that purposely hit on subjects people feel strongly about: tipping, social etiquette, and parenting. Admittedly, my posts also veered into rage bait. I designed them to be so infuriating that people would be compelled to reply and tell me I was an idiot.

As Katie Notopoulos, the journalist who did the experiment, notes:

Rage bait and engagement bait can be rage-inducing but harmless when you come across a single post. But when that type of content is flooding your feed, it's annoying. It's also an easy play for people who seek to profit from engagement.

When I asked a Meta rep what the company had to say about how Threads spreads viral content, they said: "Replies are one of many signals our systems take into account when determining what posts to recommend to people, but it's not the most important one. What you see in your For You feed is personalized to you principally based on factors such as accounts and posts you have interacted with in the past on Threads, or how recently a post was made."

Which is, of course, just EdgeRank by another name. It worked for Facebook, why shouldn’t it work for Threads?

Except that there’s one big, big problem with letting The Algorithm take over your network. And it’s that it will shape how your network behaves. Thus for example Facebook, by deprioritising news, has given carte blanche to all the AI slop that now infests it. Threads is going to become the home of ragebait in much the same way. Twitter, well, you already know about that.

It doesn’t have to be like that. You could have an algorithm which rewards people for being correct, by some sort of Community Notes-style approval system. You could have one which boosts them by their external reputation if their posts are about a topic they know about. You could do all sorts of things. But they don’t. So you see what we get. But at least now you know why.

Glimpses of the AI tsunami

(Of the what? Read here. And then the update.)

• Parmy Olson has a new book coming out about the way AI has exploded in use. She’s an excellent writer, always worth reading. (The book is called “Supremacy”.)

• Asked for the image of Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, Google served up an AI-generated version as its top hit. Search is getting broken.

• Believing what AI tells you can make you less good at your job, as evidenced by a study on some radiologists: an AI set up to give wrong answers on some scans (which humans would consider in making their decision) meant diagnosis accuracy dropped from 80% to between 22% and 45%.

• Runway is going to ingest all the Lionsgate films for the purposes of storyboarding. I’m sure it will stop there and not go further.

• The Word Frequency list (“a snapshot of language that could be found in various online sources”) will not be updated any longer because Generative AI has polluted the data: “I don’t think anyone has reliable information about post-2021 language use by humans.” (Also access to those sources has become expensive.) The web! It was nice while it lasted.

• You can buy Social Warming in paperback, hardback or ebook via One World Publications, or order it through your friendly local bookstore. Or listen to me read it on Audible.

You could also sign up for The Overspill, a daily list of links with short extracts and brief commentary on things I find interesting in tech, science, medicine, politics and any other topic that takes my fancy.

• I’m the proposed Class Representative for a lawsuit against Google in the UK on behalf of publishers. If you sold open display ads in the UK after 2014, you might be a member of the class. Read more at Googleadclaim.co.uk. (Or see the press release.)

• Back next week! Or leave a comment here, or in the Substack chat, or Substack Notes, or write it in a letter and put it in a bottle so that The Police write a song about it after it falls through a wormhole and goes back in time.

We rewatched the London Olympics opening ceremony recently (I promise my kids were genuinely interested to see it and we didn't lock them in or anything). The bit where Sir Tim Berners Lee tweets "This is for everyone" really struck me because it just doesn't feel true at ALL anymore. Maybe it never was, but for a while there it really did feel that way. Now it just feels like its the playground for a group of men who would all absolutely give women ratings out of 10.

It's a little more complicated, there are failure-modes.

"You could have an algorithm which rewards people for being correct, by some sort of Community Notes-style approval system."

One problem here is that "correct" and "popular" aren't identical. Community Notes is currently functional because it's shooting down "extremist" content. Which is laudable, as far as it goes. But extending that idea too much leads to the problem that unpopular but true things get "downvoted" (I know, everyone claims this, but it's still a problem).

"You could have one which boosts them by their external reputation if their posts are about a topic they know about."

How do you programmatically determine that external reputation and topic expertise? And do you really want to extra-boost e.g. Alan D*rshowitz? Remember, celebrity [lawyers, pundits, even scientists] have the largest public reputation. And one often gets to be such a TEDtalker by not letting facts get in the way of a good story.

Hasn't this given us the dreaded - boo, hiss, spit, choke - *techbro*? People who have big reputations because they got rich and that's taken to mean they know about society in general? (instead of course working their way up the ranks of the chattering class, which is often regarded as the true measure of who deserves listening to).

"You could do all sorts of things."

Indeed, but some of it is not so evident. And all of it costs money.