Please remain on the platform: the false gods of "engagement"

Plus even Googlers are wondering about Bard

When the point of one’s writing is the stupid or bad things that happen on social networks due to their owners/organisers cupidity, it turns out that at present not writing about Twitter1 is difficult. As you’re probably aware, that’s because the current owner is a fool.

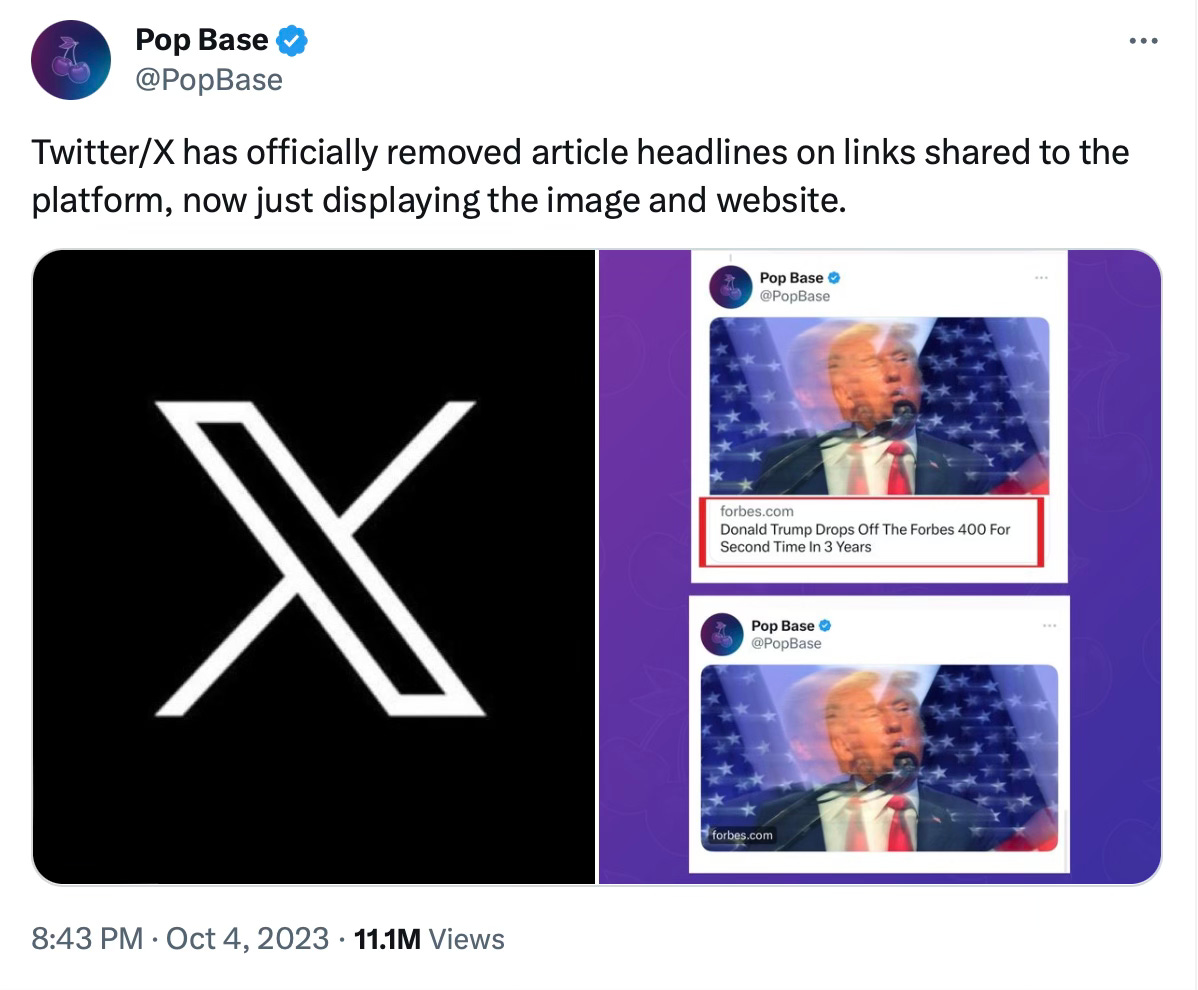

The change made at the end of last week meant that links to external sources, and particularly to news sites, stopped showing the headline of the story (which is done via a function called Twitter Cards; alternative web archive version in case that gets wiped) in the tweet.

The Card function was introduced in June 2012 (again, archive) on the basis that it

gives partner websites the option to present their content in a more engaging way on Twitter. When users expand Tweets containing links to sites that have opted in to participate, they’ll see content previews, images, videos, and more.

Over time they became more sophisticated, allowing companies to link directly to apps for download. The purpose? “Drive engagement from your Tweets”, as the developer documentation explained.

To which the new thinking, apparently, is: screw that. On Wednesday last week, the change started rolling through the network.

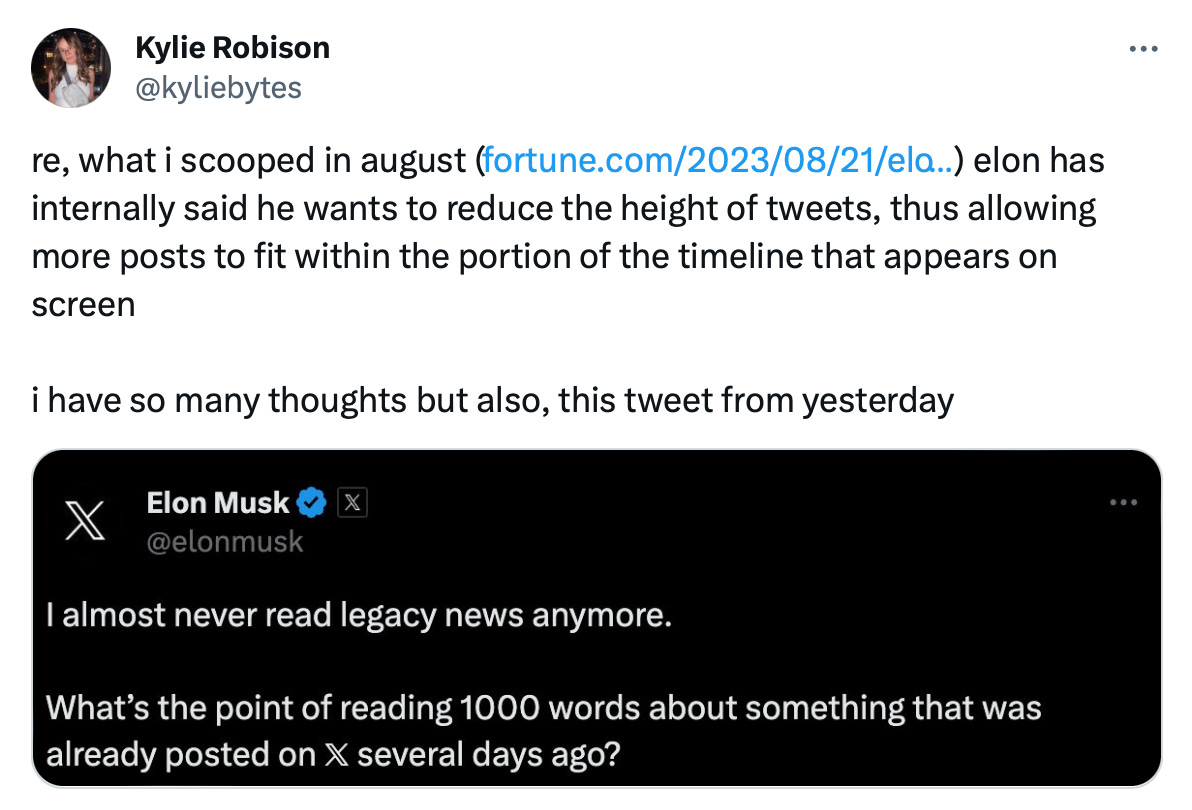

So what was the rationale? Well, it’s more like an emotionale. Here’s the owner of the platform, explaining the two parts of what we’ll lightly call his “reasoning”:

And there’s also this:

So. He wants to de-emphasise links, because they might take people away from looking at the adverts for dropshipping companies offering items that aren’t legal to sell in your country, or the Community-Noted products from big name companies. And he wants to squeeze more tweets onto the screen, because then.. you’ll read more tweets?

It’s always good, at a stage like this, to take a step back and ask: what does everyone else do? What has been tried? Is there a single formula that definitely works?

Roll back a couple of decades, and we have Google. Interviewed in April 2004, a few months before the company’s enormously successful IPO, co-founder Larry Page set out the plan he and Sergey Brin originally had:

"Other companies would boast about how users spent 45 minutes on their site," says Page. "We wanted people to spend a minimum amount of time on Google. The faster they got their results, the more they'd use it."

So: the premise of arguably the most successful single site on the internet was to make people leave it as soon as possible, by linking them to the information they wanted. Paradoxically, by sending users away, you kept them coming back. The reason: you were linking them with what they wanted—using the nature of the web.

Alongside Google in the early days was another search engine, aimed specifically at content from Usenet groups. Usenet, started in 1981, was a floating discussion board on the internet composed of “news groups” around particular topics. Like other early internet things such as email, nobody owned it and no single person ran it; instead there were groups of systems administrators who ran their own parts of Usenet according to conventions of things you did and didn’t do (for the latter, you didn’t post images into non-image groups, and you didn’t crosspost the same content into multiple groups, and you didn’t post the same content into multiple groups. As you’d expect, the latter two conventions, being anti-spamming, became the source of continuing wars between spammers and admins). You could think of Usenet as being akin to Mastodon today—federated content that gets shifted around. There were also multiple different “newsreader” programs of varying sophistication that would, for instance, let you block individuals, or topics, or groups for varying lengths of time.

Anyway, the thing about Usenet content was that it was essentially evanescent; posts would typically vanish from servers after a couple of months. Then in 1995 (two years before Google) Steve Madere in Texas had the bright idea of archiving everything on an ongoing basis. He called it Deja News. To quote Wikipedia:

While archives of Usenet discussions had been kept for as long as the medium existed, Deja News offered a novel combination of features. It was available to the general public, provided a simple World Wide Web user interface, allowed searches across all archived newsgroups, returned immediate results, and retained messages indefinitely. The search facilities transformed Usenet from a loosely organized and ephemeral communication tool into a valued information repository.

It also raised questions about privacy: what, people (specifically Charlie Stross) asked, if you could trace the stupid things people had said and posted back through the years?

What worries me is not the defeated expectation of privacy, but the inverse of privacy - a surveillance society in which you can't get away from anything you said years ago. And I believe this is what DejaNews implies.

…There will be social changes, some of them good and some of them bad. Things which are not currently considered bad will become sins, and vice versa.

Imagine that, eh? (A solution was devised: the X-No-Archive header, which could be added to a post or group as an instruction to search engines not to index.)

My point here is actually to tell you about what happened to Deja News. As the dot com boom got under way over the next six years, Madere had the bright idea of putting advertising on Deja News. He also—and this is key—made it almost impossible to exit the site once you were on it. It succumbed to portalitis—the desire to be a destination, never a jumping-off point. It turned out though that people didn’t find much benefit in rooting around old postings, nor trying to read current newsgroup postings through a web interface that was inferior to the newsreader software.

Guess what? Deja News went bust. The archive was sold to, of all people, Google, and became subsumed into Google Groups.

So when it comes to the question of “is it better to let people bounce off your platform or try to corral them inside?”, we have one piece of evidence. And before you say “ah yes but Twitter needs to show people adverts”, don’t forget that Google is funded by advertising, too.

“Portal disease” was quite common just ahead of the first dot-com crash in 2001. Websites tried to throw absolutely everything onto their front page, and offer absolutely every possible facility and tidbit of information—weather, news headlines, sports, politics, email, whatever—in the hope of grabbing and holding your attention while also beaming adverts at you. Alta Vista, the premier search engine before Google, caught a bad case of portalitis by 2001; it didn’t make it a better search engine or more desirable. Yahoo is the classic case of portalitis: the kitchen sink long since ceased to be enough. And Yahoo’s value has fallen in line with peoples’ fading tolerance for portals.

Yet Musk wants Twitter to be a portal. It’s hardly a good sign.

Let’s examine the most likely effects of the two key changes made in the past week, though.

First: removing the details of the headline from Twitter Cards. As noted above, this will mean just the image and the website show up; no detail of the headline of the story. You can’t tell if something is just an image, or actually a clickable link.

The easy prediction is that this will reduce the number of links that get clicked. But: hardly anyone clicks on links on Twitter now. Recently Axios published some data from Similarweb showing that traffic to news publishers from Facebook and Twitter has cratered in the past few years. For August, if I’m reading the graph correctly, there were 22.6m clicks to news sites from Twitter, down from a peak of nearly 80m in January 2021. (Can you think of a newsy event that happened then? The graph drops pretty rapidly after then.)

For a site with about 200 million daily users, 22.6 million clicks over 30 days works out to.. about 750k clicks per day, or just 3 per thousand daily users. And then consider how many tweets those people are seeing: in the order of hundreds per day if you spend even an hour or two there. It’s not quite one click per million tweets, but it’s only an order of magnitude away. (That’s why Twitter instituted “Want to read the article first?” for those times when you retweet something without reading the article first.)

Upshot: removing the headline might not make any difference at all, because hardly any links get clicked. In fact, the curiosity factor might even lead to some extra clicks just to see what’s on the other end. “Increased engagement” already happens. People don’t click many links. The algorithm is wasting its CPU cycles picking tweets without links over those with.

Second: removing the headline makes Cards less high so more tweets can fit onto a screen, which is a good thing because then you can spend more time on Twitter reading more Twitter content.

This is stupid. Since the graphical user interface (GUI) became a thing, some time in the 1980s, people have learnt how to scroll a page on a screen. Squeeeeeezing more tweets onto a screen won’t actually make any difference to people’s behaviour. It will just mean that Musk, who is now the only user who matters for QA purposes, won’t have to scroll so far to find more absurd nonsense and recommend it to his millions of followers.

So: two changes, neither of which will actually make any difference in themselves to the number of users, or “engagement”, or anything that makes a difference to Twitter. In trying to move the needle, it turns out that the needle is surprisingly stubborn.

What then does make a difference? That’s easier to see. Lack of moderation, the spread of misinformation and disinformation (especially by one of the biggest users of the platform), putting adverts for blue-chip brands next to extremist content, letting extremists back on the platform—these things, it turns out, will depress your user numbers, and your advertiser engagement. That’s what we’re seeing. Musk thinks he’s making a difference with those changes. But the difference he’s making is coming about because of all the things he isn’t changing.

Glimpses of the AI tsunami

(Of the what? Read here. And then the update.)

• Voice actors worry generative AI will steal their livelihoods. With good reason: the story gives an example of a voice actor discovering that her voice had been cloned via AI to “star” in steamy cartoon scenes.

• Generative AI is coming for (the boring part of) sales execs’ jobs—and they’re celebrating. Because the part of it they’re “coming for” (actually “being assigned to”) is writing the responses to RFPs, requests for proposals, which are the incredibly tedious documents that companies put out when they want bidders for a contract. Writing RFP responses is the work equivalent of going to get the coffee for the entire office, only worse. Getting chatbots to write them leaves the sales execs to do the hard work of corporate sales—schmoozing and boozing people and giving product demos for half-finished software. Let’s see ChatGPT manage that.

• Even Google insiders are questioning Bard AI chatbot’s usefulness. “The biggest challenge I’m still thinking of: what are LLMs truly useful for, in terms of helpfulness?” said Googler Cathy Pearl, a user experience lead for Bard, in August. “Like really making a difference. TBD!”

• Big tech struggles to turn AI hype into profits. Perhaps the AI backlash is under way?

• Bumble CEO Whitney Wolfe Herd shares how AI will ‘supercharge’ love with digital matchmakers. She thinks users of the matchmaking app will tell AI chatbots about themselves, and then—get this—the AIs will confer and figure out who is compatible. As Wendy Grossman commented to me, “they’ve invented the yenta.” (Properly, Wikipedia says, the shadchan, and for that misunderstanding we should blame Fiddler On The Roof.)

• You can buy Social Warming in paperback, hardback or ebook via One World Publications, or order it through your friendly local bookstore. Or listen to me read it on Audible.

You could also sign up for The Overspill, a daily list of links with short extracts and brief commentary on things I find interesting in tech, science, medicine, politics and any other topic that takes my fancy.

• I’m the proposed Class Representative for a lawsuit against Google in the UK on behalf of publishers. If you sold open display ads in the UK after 2014, you might be a member of the class. Read more at Googleadclaim.co.uk. (Or see the press release.)

• Back next week! Or leave a comment here, or in the Substack chat, or Substack Notes, or write it in a letter and put it in a bottle so that The Police write a song about it after it falls through a wormhole and goes back in time.

Twitter is the platform, X the owner company. Rather as Facebook is subsumed by Meta, or Google by Alphabet.

We can thank Cory Doctorow for the word “enshittification.”

“Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.”

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys