The trouble with video

Rewind? Who wants to rewind when you could just like and subscribe?

A few years ago I read the Sebastian Faulks novel “On Green Dolphin Street”1. Set in 1959-1960, one of its main characters is a news journalist called Frank Renzo who is under a cloud, having come under suspicion from the House Un-American Activities Committee. (Who can think of such a thing now! The very idea!)

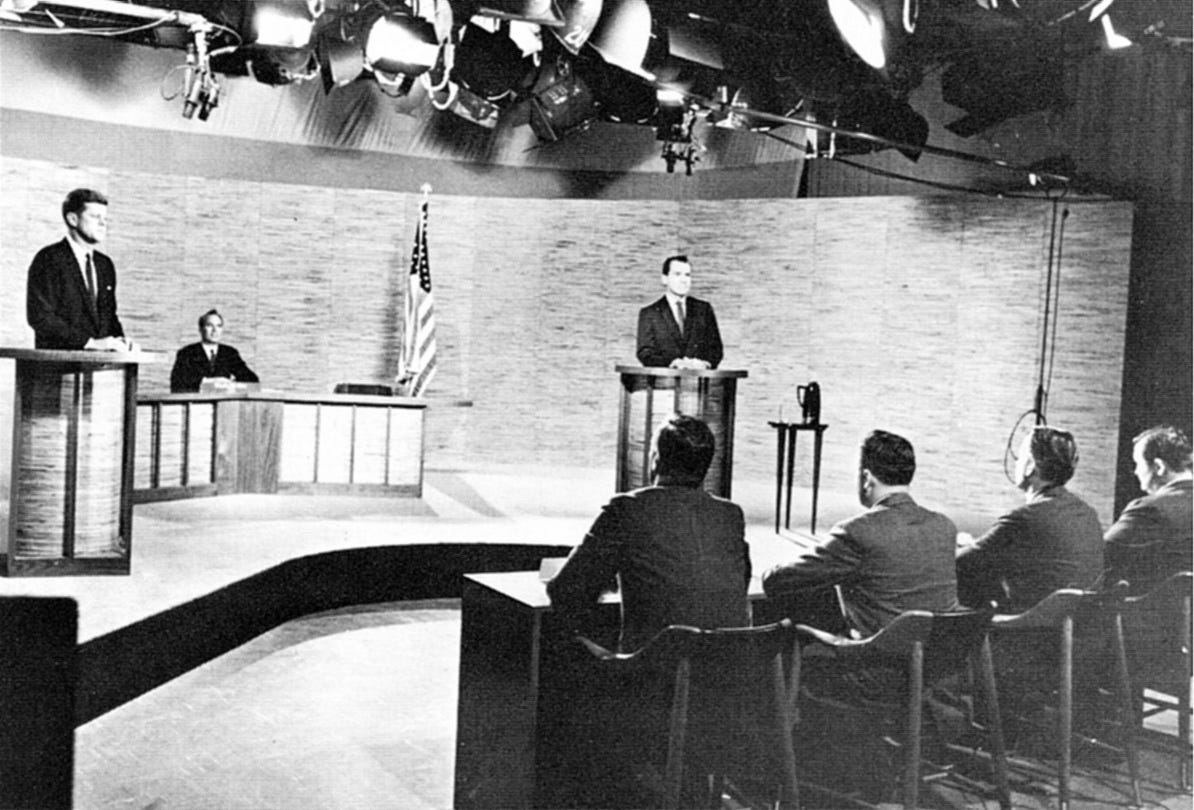

Renzo begins making his way back into the newspaper world, and is tasked with writing up the Kennedy-Nixon presidential debate. Renzo is stuck in the office, of course, taking in the debate unfold. The piece he writes suggests that Nixon had the better of it. The next day, his colleagues are incredulous: Kennedy, they tell him, was far more persuasive.

The difference? They’d been watching it on TV, while Renzo was listening to the radio. As has been repeatedly acknowledged, if you didn’t see the pictures, Nixon seemed to make a stronger case; if you watched the moving images, then you’d go for Kennedy. As the link above notes:

while most radio listeners called the first debate a draw or pronounced Nixon the victor, the senator from Massachusetts won over the 70 million television viewers by a broad margin.

In hindsight, especially given what Nixon got up to when he was finally elected, we all now think the TV viewers got it totally right.

And yet there’s the germ of a lesson in there, which I was reminded of by a thread from Rob Graham, an information security specialist, on Twitter. What I like about Rob—whose politics differ quite substantially from mine—is that he always makes me reexamine my assumptions, or else brings fresh insights to things that were laying in plain view. Such as this, quote-tweeting a post about the “underdeveloped reading skills” of American high school (secondary school, in the UK) leavers:

You might respond: how important is it to read a lengthy blogpost, though? It’s not the responsibility of high school leavers to keep Substack writers (ahem) paid. But Rob’s concern is deeper than that:

“2000 Mules”, in case you’ve not heard of it (lucky you), is, to quote Wikipedia,

a 2022 American conspiracy theory[4][5][6] political film from right-wing political commentator Dinesh D'Souza. The film falsely[7][8][9] claims unnamed nonprofit organizations supposedly associated with the Democratic Party paid "mules" to illegally collect and deposit ballots into drop boxes in the swing states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsinduring the 2020 presidential election. D'Souza has a history of creating and spreading false conspiracy theories.[10]

This is a crucial topic. Rob has spent a lot of time looking into the claims by election conspiracy theorists that the Dominion and other voting machines used in the 2020 election were “rigged”; he went along to conferences where they insisted they were going to Show Proof. But of course they didn’t show any such thing. That doesn’t matter to the conspiracy theorists, though, because it’s more important to them to have someone up on the stage who is talking about stolen elections and fraud, and pointing to vague slides which don’t in fact have the detail they claim, nor show the evidence they claim they do.

It’s the show that matters, not the facts of it.

There’s a notable divide around this: I suspect that the better-educated someone is, the more likely they are to prefer text over audio, and definitely over video, when it comes to discourse and explanation.

With text, we can pause, go back, roll the thread of an argument around in our heads. With audio and definitely with video, you have to make more of an effort to hold any contradictions in your head when you find them. Video is a frustrating medium for those used to text discourse because it’s so hard to refer back and forth. I was particularly struck by the discussion in a recent episode of the Dithering podcast, where Ben Thompson (of Stratechery) and John Gruber (of Daring Fireball) discuss whatever topics interest them. In the 28 March edition—it’s paywalled, as they all are—they discussed the life of Gordon Moore and the demise of the camera review website DPReview, with Thompson noting that a lot of camera reviewing has moved to YouTube rather than the text-heavy DPReview format:

This is sort of a reality of the web in general… I think there is a broader point about how reviews have shifted to YouTube sort of wholesale, and this has been an overall shift that has been hard for me to stomach because I just don’t like watching video. The only video I like watching is sports. I don’t like watching video reviews. Give me some text and I can mow through it extremely fast… I understand this intellectually and I write about video and streaming and stuff, but on a personal level, I know I’m the weirdo here, but it’s still disappointing.

Gruber, after noting that DPReview had done some content on YouTube, responded:

I’m like you—I’m watching the video and I’m like ‘come on, come on’. I can play with the YouTube controls and turn the speed up to 1.5x, and it’s still doesn’t go as fast as I can read. I just want to read what you say and then look at the example images from the lens or the new camera or whatever it is. My mind moves faster than video can possibly move. And, or, when I’m listening to a podcast I’m doing something else.

The frustration of the well-educated with video contrasts strongly with the people who follow those we tend to think of as stirring up trouble. These people love those who rely on the spoken word (think of Trump’s speeches, which when written down are total word salads) or videos where the tumbling nature of the discourse makes rational examination impossible, while dragging impressionable people in; think of Russell Brand, who has become notorious for the bizarre nature of his video channel yet has an army of devoted fans.

I agree with Thompson and Gruber and Rob Graham above: video is a problem if you’re the consumer, trying to evaluate some content quickly and with maximum efficiency and also apply critical thinking to it. It militates against all those things: it imposes a slow pace to provide minimal content (TV newsreaders speak at about 150 words per minute; the typical adult can read at more than 200wpm, and university graduates can manage 300wpm+) and can distract the hell out of you. You can miss an argument (and especially the flaws in it) without noticing. Sure, video can show you things that words and even pictures cannot. (It can show you what a Roger Federer backhand looks like in a way that words cannot—though it was written words about Federer, these ones in particular, that alerted me to the fact that I should try watching tennis again, after a 10-year break.) When it comes to persuasion and argument, it’s the written word that tends to carry the power.

Ironically, this is exactly what makes Twitter so attractive to people who don’t like video. As a text-based medium, it’s ideal for the back-and-forth that text-based people treasure. Certainly that brings its own penalties, but I rarely see arguments settled by reference to a YouTube video.

So what’s the social warming message? Graham points to it: you’ve got a large number of people who are functionally illiterate when it comes to longer pieces of argument but who are happy to accept the claims made in videos: think of 2,000 Mules and the Plandemic video (which claims Covid was all planned long ago). When people don’t know how to examine what they’re being told, they’re vulnerable to being lied to. And that’s what video enables. Which in turn means that they’re vulnerable to being manipulated, turned against putative enemies, encouraged to hand over money to grifters, and generally exploited.

And meanwhile video is an increasingly popular medium. Ask Facebook, ask Instagram, ask—of course—TikTok and YouTube.

Is there a solution? Perhaps if those people referred to back in the Politifact tweet were taught how to examine what they’re being told through these media in school. That does sound a little like begging the question: you’re trying to teach people who aren’t good at critical thinking to do critical thinking? That is the point of schools, though: teaching you how to get better at doing things you’re not so good at.

Well, we can but hope. Like and subscribe, why not?

Glimpses of the AI tsunami

(Of the what? Read here.)

• Wizards get paid for spells. Well, prompt engineers (who come up with the incantations for the AI systems) who can command salaries of $335,000 or perhaps more.

• Le sigh: “the deepfake AI porn industry is operating in plain sight”. Of course it is, with credit cards accepted and everything.

• Stop, please, stop! More than a thousand AI-adjacent people signed a letter asking—nay, demanding—a six-month pause in work on LLMs “so the capabilities and dangers …can be properly studied and mitigated.” Reminds me of the moratorium on genetic modification of bacteria in the 1970s.

• Calm down, folks: ChatGPT isn’t an actual intelligence. Yes, this is what we’ve been trying to tell you, but will the Daily Mail listen?

• The LLMs are really coming for the programmers’ jobs. This makes a lot of sense if you think about it: programming languages have very strict grammar and very limited vocabularies—quite unlike natural languages—and programs are the melding of statements in that language to express an output. Framed like that, you can see why huge numbers of GitHub programmers now use Microsoft’s CoPilot AI assistant.

• As a programming note, this section is rapidly approaching the point where, as with tsunamis, it’s overwhelming trying to stay abreast of it.

• You can buy Social Warming in paperback, hardback or ebook via One World Publications, or order it through your friendly local bookstore. Or listen to me read it on Audible.

You could also sign up for The Overspill, a daily list of links with short extracts and brief commentary on things I find interesting in tech, science, medicine, politics and any other topic that takes my fancy.

Yes, I recommend it.

Add this to what the Netflix documentary Unraveling the Mind teaches about the psychological side of conspiracy theories, and you get the actual reality.

There is a reason that right-wing governments like to disembowel education, libraries, and any other edifice of knowledge and critical thinking.

Though we focus on reading skills – and we mustn't get too smug in the UK given a quarter of our 11 year olds do not read/write to the expected standard – an equally large problem which I do think plays into the lack of critical thinking skills is innumeracy. Only 22% of British adults are functionally numerate, which means that the vast majority are swamped by numerical information.