The idea of the wisdom of crowds is quite well known; the journalist James Surowiecki wrote a book of that name in 2004, distilling a lot of what had come to be understood about the phenomenon that was best crystallised by Francis Galton. To quote from Wikipedia:

The classic wisdom-of-the-crowds finding involves point estimation of a continuous quantity. At a 1906 country fair in Plymouth, 800 people participated in a contest to estimate the weight of a slaughtered and dressed ox. Statistician Francis Galton observed that the median guess, 1207 pounds, was accurate within 1% of the true weight of 1198 pounds. This has contributed to the insight in cognitive science that a crowd's individual judgments can be modelled as a probability distribution of responses with the median centred near the true value of the quantity to be estimated.

You can read Galton’s original paper, which shows that it was 787 people (actually) who voted and that their estimates varied from 1074 to 1293 pounds—that is, from -11% of the true weight to +8%, or nearly a fifth of the weight in total. Galton makes the point that the distribution of estimates meant any randomly chosen measurement has a 50% chance of being within +/-3% of the correct weight.

But, as he also notes, there were plenty of experts among those making their estimate, including butchers and farmers (with a sixpenny—half a shilling—entrance fee to dissuade jokers). Strangely, the estimates erred towards a higher value: “I have not sufficient knowledge of the mental methods followed by those who judge weights to offer a useful opinion as to the cause of this curious anomaly.”

Crowd psychology is a strange thing: we don’t necessarily know how people arrive at the decisions they do. Surowiecki gives lots of examples and anecdotes in his books; the idea is that we ought to think crowds have access, almost through the Brownian motion of their thoughts, to insights that aren’t available to individuals.

Certainly it’s true that if you ask a large enough group of people a question requiring specialised knowledge, you’ve got a good chance of finding someone who knows all you need to know about that topic. You might even find two people; if you hold a fair with slaughtered dressed oxen and have a lot of farmers and butchers around, they’re probably going to be better at guessing than if you ask a bunch of children. The idea that the crowd was probably wiser than us was a big idea at The Guardian when I joined it in 2005—that writing and publishing a story wasn’t the end of the process, because now the readers could feed back their ideas to us.

This idea was warmly embraced, particularly by opening up the space below the articles to comments about their contents. These were not always supportive. They were not always anything to do with the article. They were not always legal and they were sometimes just excessively offensive, and so people had to be hired to monitor what had been written in the comments. Sometimes they found good stuff too, but it was like trying to pan gold in a sewer.

The wisdom of crowds seemed to be more about the crowds part than the wisdom part. And this was only 2004/5—predating widespread access to social media that we would recognise now. (We’ll ignore FriendsReunited and MySpace: the former wasn’t “social” as such, the latter died within a couple of years.)

And then as Clay Shirky observed, “here comes everyone”. Social media arrived, and the crowds and the question of their wisdom moved onto Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and so on.

There was a period in the mid-2010s when you could probably say that Twitter (as previously formulated) could do a pretty good “wisdom of crowds” exercise. Its use of verified accounts that were actually who they claimed to be, the scale of its user base, meant that asking a question might get a useful answer. It was the world’s telephone book, or the people who knew who to contact in the telephone book.

And now? Upheaval! If you focus only on the past three weeks, the utter insanity of the crowds has been on show. One of Charlie Warzel’s contacts called the process that’s going on right now the “rapid unscheduled disassembly" of the US government”1. Elon Musk is leading an attack on, basically, anything that costs money, and his gimlet eye has fallen most quickly on the Department of Defense, with its $850bn annual budget which surely has colossal amounts of waste.

Just kidding! He went after USAID, which employs about 100,000 people doing various sorts of soft power things around the world (eradicating disease, feeding starving people, monitoring epidemic outbreaks such as Ebola) with a budget of around $40bn.

To help slash and burn its activities, he and lots of people adjacent to the White Madhouse turned to usaspending.gov, which lets you search by name, award, amount, all sorts of things. Of course they inquired what USAID had been spending its money on, and were suitably outraged at many of them. Helping people not to die? Preventing Ebola getting so big that someone couldn’t just get on a flight to the US while ill and spread it? Wasteful nonsense!

It also demonstrated that a crowd with no idea what it’s doing with a database is about as good for the public discourse as a child given a box of matches and an open can of petrol.

There are hundreds of examples of this sort of thing. At one point, the finger-pointing right-wingers triumphantly discovered that the US Treasury pays money for Bloomberg terminals. Imagine! People in government finance knowing what’s happening in the bond markets? Intolerable!

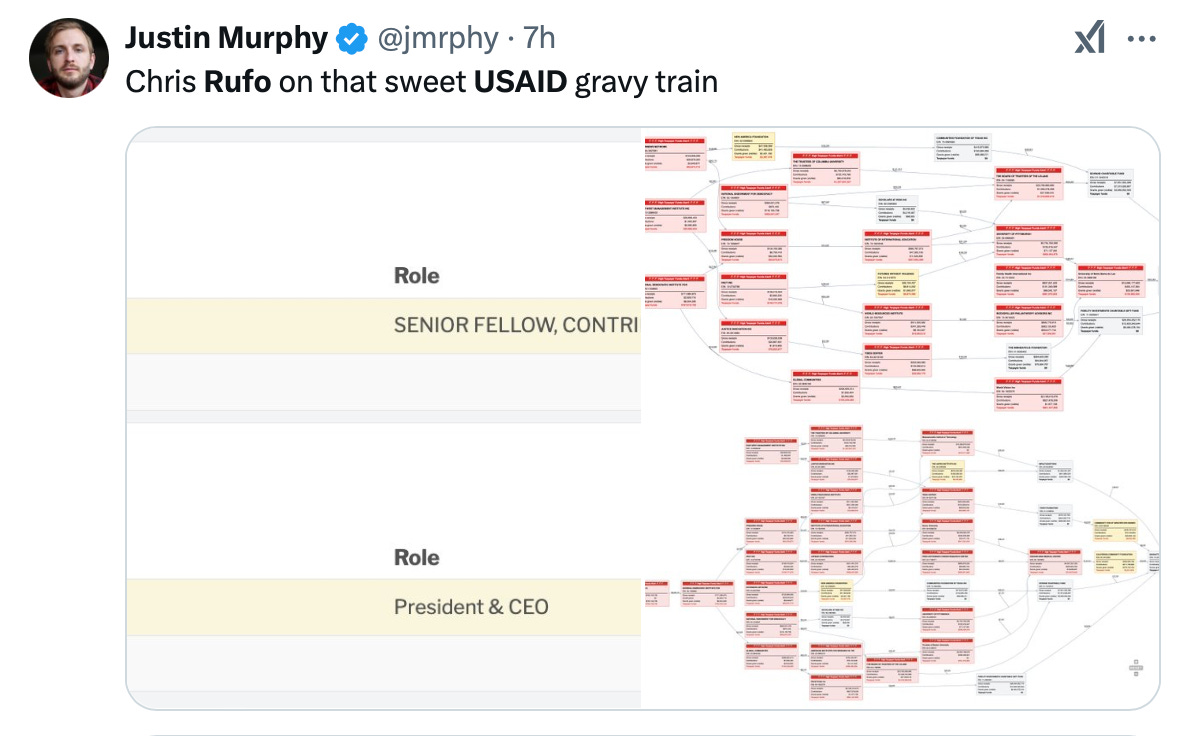

At another point, the finger-pointing turned into a circular firing squad and/or ouroboros. (Chris Rufo is a prominent right-winger in the US.)

Which unsurprisingly earned a pretty rapid response:

And then:

Gee, d’ya think that it’s at all possible that a colossal crowd of people all slamming a site they don’t understand could possibly have bad outcomes? (See more for yourself with this search. Hilarity and headshaking at humanity’s ability to get the wrong end of the stick guaranteed!)

But here we are. The wisdom of the crowds has given way to the utter madness. Although by contrast the same search on Bluesky yields a rather more rational set of takes, even if their vehemence is quite similar.

What were the inciting points in the crowd shifting from wise to mad? Obviously there’s the external political climate, and the insane claim by Musk that he will cut $2 trillion from the US budget, which simply isn’t feasible unless he closes the US military for a few years. However, if it were still Twitter rather than X, with verified accounts being people who you could rely on rather than those with questionable financial choices, I think the noise would have been tamped down. That probably wouldn’t have stopped people going on USAspending.gov and doing insane searches (if you’re willing to believe it, Jeffrey Epstein was a recipient of its goodwill) but as with a fire, what it needs to continue is both oxygen and fuel. The oxygen of a social network tuned for rightwing outrage, and the fuel of lots of outraged people who don’t really know what they’re doing, has created the perfect conditions for things to go very, very wrong. The way that stories now can bubble up from social media outposts to the inside of the Oval Office is quite scary, and so there’s cause for concern about what on earth is going to happen next. Though perhaps they will decide they don’t need tanks, or guns, or soldiers.

All I can say is that I’d be a lot more worried if I lived in the US. As it is, I have a visit planned for September and I’m already hoping that it will be functioning roughly as it was at the start of the year. But, you know, anything could happen.

A reference to one of Musk’s rockets which blew up four minutes after launch. SpaceX hadn’t expected it to return to Earth in anything but bits, so the disassembly was not a problem.

Clay Shirky's comment was delightfully apt.

I would just note that the actual phrase, "Here comes Everybody", was of course not original to him, notably used as the title of Anthony Burgess's book on 'Finnegans's Wake', and I think I recall a use from the Forties, though I could be wrong.

The point you make about not merely propagandists but whole crowds using words to lie to themselves with is well taken.