What really happens when you work with AI

Plus impossible (and possibly inedible) recipes imagined by machines

Last week I wrote about a paper published about a decade ago which pondered whether some jobs might be more susceptible to being taken over by AI than others, and if so which those would be. I suggested that what might be more likely would be that humans would work alongside the AI, becoming even better versions of themselves: “centaurs”, in the word used by chess champion Garry Kasparov about human chess players working alongside chess computers to play games.

In this next instalment, we actually have an example of what does happen when humans do, and don’t, have an AI to help them with their job.

The job, or jobs, in question are tennis umpiring and line calling. This is an amazingly difficult job. At the professional level, the ball is travelling at 200km/h (125mph) or more on a serve, and groundstrokes at up to 125km/h (78mph). Line judges have to make calls accurate to 1mm within a second of the ball landing, as it travels laterally across their line of view. If the ball touches the line at all, it is in; 99% out is still 1% in. Even more tricky, the ball deforms a little on impact, so during that deformation it might expand from being juuuust outside the line, to touching the line.

And yet—protestations of John McEnroe notwithstanding—line judges almost always get this right. Occasionally they don’t, in which case the chair umpire is expected to overrule them quickly, despite the fact that they’re sitting about 7 feet above the court, in line with the net. For years, that’s how it worked; at some lower-level matches, there weren’t even line judges, just the chair umpire bravely calling the lines as s/he sees them. (At the junior level, each player calls the lines on their own side. As you might imagine, this leads to some almighty rows.)

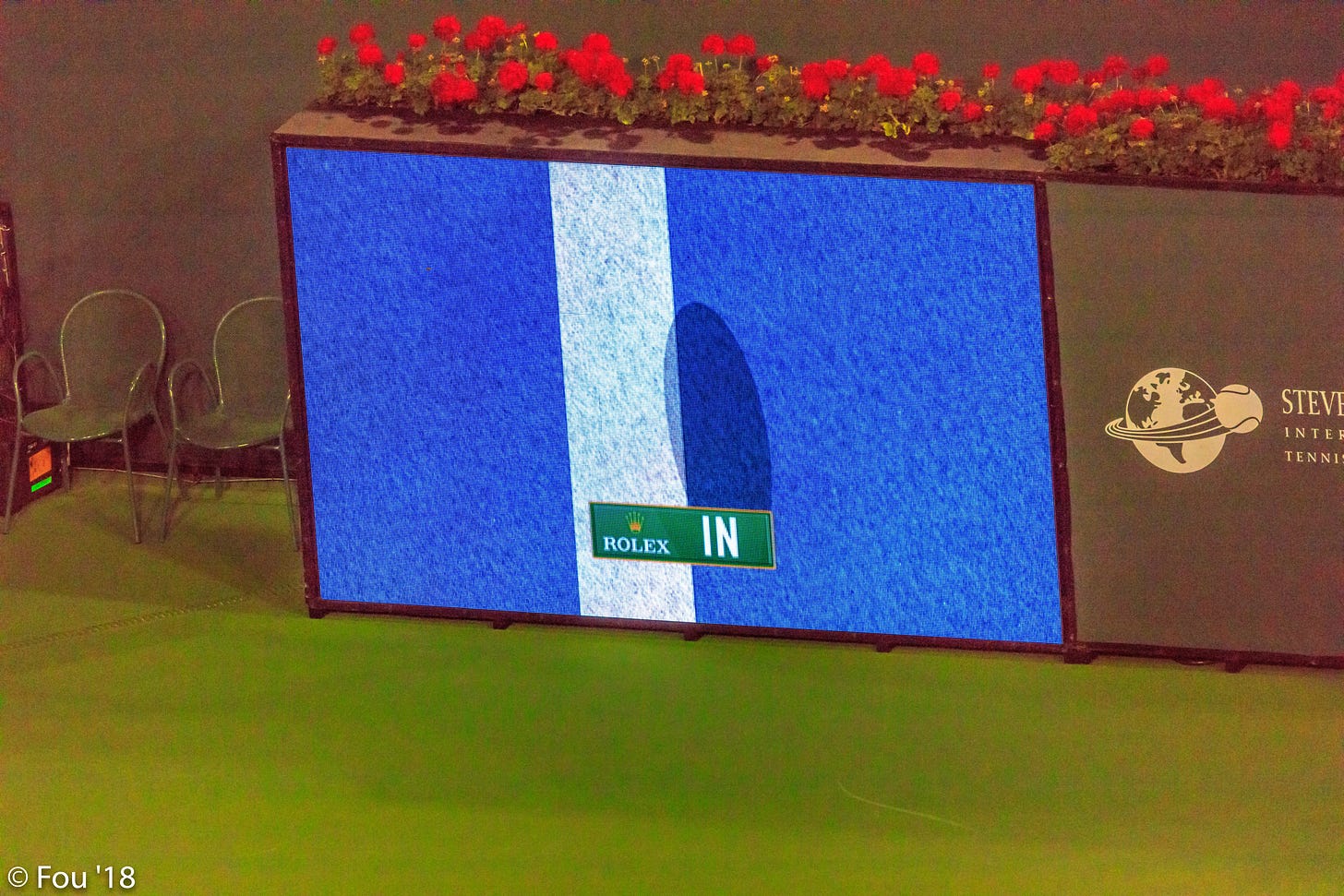

But from about 2005, a company called Hawk-Eye began offering a system to tennis tournaments which used up to 10 cameras carefully situated above and around the court feeding into a computer to generate a 3D simulation of each shot’s trajectory. The first official use was in March 2006, and since then it has increasingly colonised the job of the line judges. Covid hurried this along in 2020 at the US Open, where many matches used it, and the 2021 Australian Open (one of the four biggest events of the year, alongside Wimbledon, the French Open and US Open) only used Hawk-Eye to make calls: this “electronic line calling” (ELC) effectively made line judges redundant. (The ATP, aka men’s, tour will make ELC standard throughout events from 2025. That doesn’t, however, include Wimbledon or the French Open, nor the US Open and Australian; they’re not strictly part of the ATP tour.)

Chair umpires are still needed to call the score and some of the little niceties of the game such as service lets (when the ball touches the net on a serve—decided, for at least 25 years, by an electronic sensor, but the umpire has to announce it).

Hawk-Eye is remarkable. It can analyse not just how quickly the ball is travelling, and in what direction, but also how quickly it is rotating: topspin (turning forward in the direction of travel) and backspin (the opposite) are big weapons for professionals. Spin also has a radical effect on the flight of the ball: topspin makes it arc downwards, backspin makes it float. The cameras and particularly the computer can analyse that in following and mapping the path of the ball. The data it collects about spin and speed is all immensely valuable—which is why Hawkeye Innovations (the company) has a good business selling data to the players and their coaches.

In most tournaments, Hawk-Eye is still just used as a backup. Line judges and the chair umpire still rule, and each player or (in doubles) team had three challenges per set: if a player thinks a call is wrong, no matter where on the court, then it will be reviewed by Hawk-Eye which will deliver a final judgement. (If the player who challenged was wrong, they lose one of their challenges1; when they have none, they can’t make any more that set.) The chair umpire then decides whether the point was already over, or needs to be replayed; in the case of a serve wrongly called out, whether it was in fact been an ace, or if the call put the receiver off making a good shot. This latter can happen if the chair umpire overrules the service call, or any part of the point, because the chair umpire—when they’re being the final arbiter of live calls—can overrule the line judge: a ball might be called out, but the umpire overrules that and says it’s in, and the player challenges (on the basis they think it’s out) and then Hawk-Eye rules that it’s in. Two people were wrong—the line judge and the player—and the umpire was right. Hawk-Eye is treated, nowadays, as being as infallible as a pope. Possibly more.

You cannot be serious

You might think that leaves no room for dispute. You’d be wrong. In Dubai earlier this week, Coco Gauff hit a serve, the line judge saw it as in (hence made no call), her opponent hit it into the net, and the umpire (wrongly) called the serve out. The Hawk-Eye review showed the ball was in—but the umpire, again wrongly, thought he had called it out before the opponent hit it, and so demanded Gauff serve the point again. She refused (because if the call came after the opponent hit the ball, there was no “interference”, so the point was over), and spent a good while demanding (quite politely, in the circumstances) that he call out the supervisor to adjudicate on his adjudication. (I recommend following those two links to Twitter, because you’ll be amazed first at how wrong the umpire is, and second at what McEnroe might have done in the circumstances.)

Now, the umpire may well have believed he made the call before the ball strike; indeed, his absolute insistence suggests he did think that. But he was wrong. (He was also wrong to deny Gauff the supervisor, but that’s beside the point.)

In this situation, ELC—handing the line calling job over to the machines—would have prevented all of it. The service call would have been correct (as it was) and the umpire would have had no reason to overrule it, because umpires are not allowed to overrule the infallible ELC. So that would have been point over.

The centaur on the court

Now, that’s an instance of how things can go wrong. Yet the mixture of Hawk-Eye and humans has actually made humans better at calling lines. In a preprint by a group from Northwestern University, Deakin University and the University of Queensland, a deep analysis of hundreds of matches where Hawk-Eye was used as a backup (and so could also be used to review every shot, even those which weren’t called or challenged) shows that the line judges and umpires shifted from wrongly calling balls out when they were in (which interrupts the point) to wrongly calling them in when they were out—but doing that less often than either. The mistake rate fell by 8%, which is considerable given that the ball crosses the net hundreds of times in a match, and particularly that when the ball bounced within 2cm of a line, the human call was wrong nearly one-third of the time. (That doesn’t necessarily mean the ball was called out; they might have missed an out ball, thinking it was in, and letting the point continue. It’s also very infrequent.) For serves, the mistake rate actually went up for the very close calls—but again the humans were mostly calling balls in that were in fact out.

Why? David Almog, the lead author, suggests it’s because of shame. Having your decision reviewed in public, in front of hundreds or thousands of people—perhaps even millions, if it’s a big TV event—is not a lot of fun, particularly if it turns out you were wrong. “For umpires [including line judges], improperly stopping a point (calling a ball out when it was actually in) became a new cause of concern with the introduction of Hawk-Eye,” the paper notes.

Such errors “carry two psychological costs: one from the impossibility of implementing the correct outcome (continuing the point) and another form having to implement an arbitrary decision that, in many cases, unleashes the outrage of the players involved and the audience.” (Neither line judges nor umpires seems to get sanctioned over mistaken calls as far as anyone knows. But you can imagine that in another job, your employment might be in peril if you were shown up by the AI too often.)

It’s a weird thought that having the AI staring over your shoulder might make you better at something. But on reflection, if you’ve used Microsoft Word then you’ll have had the wiggly red lines under your misspellings, or the wiggly green ones under your ungrammatical sentences. You can ignore them, but it’s probably a mistake to. (Not in the case of “Gauff”, thanks, computer.) We’ve become accustomed to computerised oversight: it tells us about how long it will take us to drive somewhere (even if it doesn’t always recognise routes that take one-way streets), keeps track of sunrise and sunset (well I always want to know), keeps track of your exercise and footsteps (and warns you if you slack), can use a wearable to spot tiny variations in your heartbeat and warn you about them. It does things we don’t even understand to the “unedited” pictures we take with our smartphones, and then it offers all sorts of magic to the “editing” we do to those pictures. Delivery drivers are used to have a spy in the cab that can tell if they’re driving their vehicle efficiently, which maps out the best route for them, tells them how long they can expect to take between stops. If AI is looking over your shoulder in your work, that’s only to be expected. It’s been happening for years. We just didn’t give it the same name.

But the lesson from the tennis world is that the oversight can help. It can make us better. You just need to learn to live with the occasional bit of public shaming.

Glimpses of the AI tsunami

(Of the what? Read here. And then the update.)

• ChatGPT users puzzled by bizarre gibberish bug. Now you can see that it’s nonsense without having to test it on humans for irritancy.

• Adobe adding “conversational AI” to PDFs with AI Assistant in Reader and Acrobat. Who needs to read stuff? Just get your AI Assistant to summarise it. (Get your revenge on anyone you think is using this by including extracts from Jabberwocky in the long PDF you send them: they’ll think their AI has glitched. “Frumious? Snicker-snack?”)

• AI search is a doomsday cult. Ryan Broderick’s excellent Garbage Day email gets a big medieval on the bonkers idea that what we want search engines to do is summarise the internet, rather than pointing us to an authoritative site. This is, in its way, the web corollary of Adobe’s AI Assistant for PDFs: why bother reading, when you can get a computer to read for you?

• Google apologises for ‘missing the mark’ after Gemini AI generated racially diverse Nazis. Producing images is always fraught—even more than generating text—and of course Gemini didn’t survive this stress test. Rather as no plan of war survives first contact with the enemy, no AI image generator survives contact with the wider internet.

• Why the New York Times might win its copyright lawsuit against OpenAI. The authors are Timothy Lee, a journalist at Ars Technica, and James Grimmelmann, a law professor who has taught courses on IP and internet law. Personally, I’m not persuaded, because they use past cases which aren’t exactly congruent with the present (the MP3.com one, for example, where a company ripped tons of CDs and would let you stream them if you could “prove” you owned them: very obvious commercial infringement, as the courts found; not comparable with the NYT one).

• Instacart is using AI-generated images of weird recipes. Unless you’re hankering after “Watermelon popsicle with chocolate chips”, you might want to give these a swerve. “This recipe is powered by the magic of AI, so that means it may not be perfect,” Instacart helpfully informs people. Or, come to that, edible.

• You can buy Social Warming in paperback, hardback or ebook via One World Publications, or order it through your friendly local bookstore. Or listen to me read it on Audible.

You could also sign up for The Overspill, a daily list of links with short extracts and brief commentary on things I find interesting in tech, science, medicine, politics and any other topic that takes my fancy.

• Back next week! Or leave a comment here, or in the Substack chat, or Substack Notes, or write it in a letter and put it in a bottle so that The Police write a song about it after it falls through a wormhole and goes back in time.

This is absolutely what should happen with VAR in football (soccer, in the US). Don’t leave it to the referees to dither about; give the touchline coach or the on-field captain two or three challenges per half, and let them decide when to hold the game up. Squash also has a challenge system, but for obstruction rather than line calls, and only one per player per game—which rarely seems enough.